- Home

- Alison Wisdom

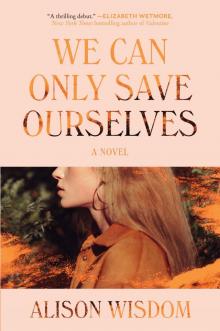

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Dedication

To my family

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

IN OUR NEIGHBORHOOD, the streets were dark for many years. There weren’t enough lamps to light the streets properly, only a few per block, shining like small yellow planets in the dark. We had porch lights and glowing windows illuminated by table lamps; we had the stars and the moon.

Now the world is different: there are lampposts every few houses. So much brightness. “Every time I look outside in the evenings, it looks like an alien invasion came down to earth,” April Morris complains to Bev Ford one afternoon. “I half expect to see a UFO floating over your house.” The new lights are tall and silver with odd fluorescent heads, the wiring inside of them visible under the surface, like brains. The women sit on lawn chairs in April’s yard watching Billy and Tim throw a football back and forth in the street. April holds a drink in her right hand, and Bev holds the baby, a tiny girl who chews on her hands and leaves a dark circle of drool on her mother’s shoulder. The baby is wearing her brother’s old clothes. People always think she’s a boy; they congratulate Bev on the little gentleman. The rest of us would correct the stranger. “A girl, actually,” we would say. “Isn’t she beautiful?” Yes, they would say.

“It’s safer,” Bev says now, “with the lights.”

“Is it, though?” April asks. Unconsciously, her eyes flit over to the Lange house.

“You don’t have a daughter,” Bev says. “You don’t understand.” They both look at the baby. She has her father’s short eyelashes, a swirl in her fine hair at the back of her head. Bev reaches up and dabs at a glistening wet spot on the girl’s chin and then sticks her fingers in the baby’s mouth. Her gums bulge, and she bites down, trapping her mother’s finger until she wiggles it free.

“She’s getting more teeth,” Bev says.

“So many so early,” says April. “That’s good.”

“Yes,” Bev agrees. “She’ll need them.”

April doesn’t say anything, and they watch the boys tossing the ball—Billy is more athletic than Tim, catches it every time, and when he throws the ball, it spirals prettily, like the pattern inside a seashell—and they don’t leave until the lights come on, filling the street with an otherworldly glow. We think of Alice Lange often in moments like these. Even if we don’t want to, even if we shouldn’t, we hope there is good light where she is, that the streets are safe and bright, that she isn’t afraid.

Chapter One

WE ALL SAW the man in our neighborhood on the same day. But there are always men in our neighborhood, and they’re relatives or fathers of playdates or old college roommates, still bachelors, their beards and clothes and cars out of place among our clean-shaven husbands and their practical automobiles, their sharply cut suits. We always notice the outsiders, but we are rarely alarmed. This is not the kind of neighborhood where we need to be.

Even as he drew nearer, passing in front of our houses, his presence registered, but that’s all. Those of us inclined to take more careful note of outsiders did; those of us who are not did not. Mrs. McEntyre, for one, always notes the kind of shoes people wear. It’s a cautionary measure, she says, in case, somewhere down the line, the police need as many details as possible.

This particular man wore boots. The color: brown, faded under a layer of dust or dirt. Toes: pointed. Rise: unknown; they were hidden beneath his jeans, the legs of which were stovepipe straight. Mrs. McEntyre almost forgot to notice the shoes entirely, though, because as he passed her on the sidewalk, her dog, Sweetie, did not bark. Sweetie has barked at all of us, even though we’ve known her since she was a young pup, turning herself in circles in the front yard and nipping at the calves of all who passed the McEntyres’ threshold. But this man walked right past the pair of them, woman and dog, and Sweetie was still. “She always barks,” Mrs. McEntyre found herself telling the man as he went by, then reminded herself to look at his shoes.

He didn’t slow down, but he smiled at her, then said over his shoulder, “Animals always like me.” His voice was deep and pleasant. Soft and somehow pliable, the way she imagined the leather of his boots would feel. Across his chest was a brown leather strap attached to a small bag, almost, Mrs. McEntyre thought, like a lady’s purse, but it didn’t seem out of place. He wore it the same way a person wears his arms, his legs, the hair on his head—naturally, organically. She didn’t watch him as he moved down the sidewalk, but only a moment later Sweetie barked, and Mrs. McEntyre looked over her shoulder, and the street was empty.

On another street, a few turns away from where Mrs. McEntyre strolled with Sweetie, a group of children playing soccer saw the man, too, but barely noticed him. Those who did saw an adult, expecting him to tell them to get out of the street, to watch for cars, to go in and wash up for dinner. Billy Morris squinted up at the sky. It had been cloudy all day, and it had barely changed color from hour to hour, but the sun had begun to set, and the bearded man would have been right if he had told them it was time to go home. But he didn’t. Christine Pittman kicked the ball in his direction, hoping—what? That he would come play? That he would speak to her? But it hit the curb and rolled back to her. “Nice one,” Billy Morris said. The man kept walking.

April Morris, Billy’s mother, was on the phone with her neighbor across the street, watching the kids outside through the window above the kitchen sink. Her fingers wrapped up in the curls and loops of the phone cord, she leaned back to see the time on the stove. “I’m going to have to go in a sec,” she said. “I’ve got to get Billy back inside and into fresh clothes before Eric gets home. Has Tim gotten horribly smelly lately, too?”

“It’s too awful,” Bev said on the other end of the line. “It’s ungodly. I can’t even talk about it. Why can’t they all be girls?”

April laughed. She turned and leaned against the sink, her back to the window. “You know why,” she said suggestively. Bev was seven months pregnant. April waited for her friend to respond (Bev has a quick wit, though sometimes too much so) but she didn’t say anything. “Bev?” April said.

“Sorry,” Bev said, “I got distracted. Some guy just walked past the kids, and it looked like Christine Pittman was going to kick a ball at hi

s head.”

April turned back around and looked out the window. The game was back on, Billy winding past the other boys, kicking the ball carefully, skillfully, as though it were an egg that might break if he was too forceful. She looked down the street and saw the broad back of the man Christine had nearly hit with the ball.

“Who was he?” April asked.

“Who?” There was a hissing sound that puzzled April until she remembered Bev’s phone was anchored to the wall near where the ironing board unfolds.

“The man on the sidewalk,” April said.

“I didn’t know him,” Bev said. “He was young and had a beard. Dark hair.”

“Hmm,” said April, and she was about to say she had to go, had to call sweet, stinky Billy inside, and she could tell Tim to go home, too, if Bev wanted, when Bev said, “He looked at me.”

“The man?”

“Right into the window,” Bev said. “It was odd.”

“Was he handsome?” April said, teasing.

“Yes,” said Bev, but her voice was funny when she said it, like maybe he actually wasn’t, or like it wasn’t a good thing to be that kind of handsome, to look the way this man did. April wished she had seen him, too, not just the back of him.

“I should go,” April said.

“Me, too,” said Bev, and the women hung up. Seconds later, they waved at each other from their doorsteps as they called their boys back in.

Later, Earl Phelps said he’d had the feeling he was being watched by someone he couldn’t see himself, but when he looked around, there was nothing out of the ordinary. The strange thing was that it was only then, after he had cleared the area and judged no incoming danger, that he saw the man rounding the corner and coming up the street. He told us he noted the man’s hair and beard but his jacket was what caught his eye. It was army green, canvas. These young people, Earl said, their military-style clothes, and they didn’t even have respect for men like him, men who had served their country, who had fought and watched people die. “Howdy,” the man said as he passed, and Earl gave him a begrudging nod. Beyond the military jacket, he was a man carrying a woman’s purse, and Earl didn’t care to speak to him.

The last person to see the man in the neighborhood before he got in his car and drove away was Alice Lange. Alice Lange, the beloved, the beautiful! She would be crowned homecoming queen in two days. This was an unofficial prediction—the ballots had only just been cast and now sat in a box in the principal’s office—but everyone knew she would win, because who else could it be? It had always been her, from her first day of kindergarten, when she had two skinned knees and a red ribbon in her hair; to fifth grade, when she socked Randy Neely in the stomach because he insulted her friend (and she wasn’t even punished for it); to junior high, when she hurried out of her volleyball uniform and into her cheerleading skirt and onto the sidelines to cheer on the football team, because she could do it all, our girl; to high school, where the girls loved her, the boys loved her, the teachers, the parents, the women who scooped macaroni and cheese in the lunch line loved her. Yes, it had to be Alice Lange.

And no one else for this man to see than Alice Lange. She was on her porch swing with a book when he passed by, and he stopped and stood still on the sidewalk in front of her. “What are you reading?” he called out to her.

“Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” she said. She wasn’t surprised to see him or to hear his voice. It seemed to her a perfectly natural question. She was a girl reading a book, and the cover was obscured from his vision. Why wouldn’t he ask?

“A classic,” the man said. “Do you like to read?”

“I do,” she said. “Do you?”

“Yes,” he said. “Hey, can I take your picture? You don’t even have to move.”

Alice must have looked hesitant because he held up both hands, as though he were showing her he wasn’t armed. “I’m a photographer,” he said. He tapped at the bag on his hip. “My camera’s right in here.”

“Oh,” said Alice, relieved. “Okay. Yes. Here? Or?”

The man grinned. His teeth were worth noticing, though so far only Mrs. McEntyre had seen them. He’d smiled only at her and now at Alice Lange. They were straight and white, though maybe it was only that his skin was so tan, like he was a man who worked outside, on a ranch, on a farm, in the hills, on a dock somewhere outside the city. His eyes were bright, too, a brilliant blue, like the lightest part of the sky on a spring day.

“There. Don’t move,” he said. He walked up the stone pathway to her house, and Alice watched him as he approached, as he got larger and larger until there he was in front of her. He was like the sheer face of a cliff or the ocean, something vast. She could see nothing else.

He opened the camera bag and lifted the camera out. “Smile,” he said.

“I don’t want to,” said Alice, lifting her head regally. “I don’t feel like it.”

“Okay,” he said. “That’s cool. It’s whatever you want, girl.” It was always whatever Alice wanted; we had told her that all her life. We would give her anything, but when the man said this, she felt somehow more powerful than she ever had before. Now, she thought as he took her picture, she was the ocean. She was the vast, wild thing.

“Thank you,” the man said. “What a gift.”

“Could I see the picture?” asked Alice.

“Soon,” he said. “I’ll be seeing you again.”

“I suppose you will,” Alice said. Neither of them said good-bye, and the man walked away, but Alice felt like he hadn’t really left at all, that part of him was still there.

Alice read a few more pages and realized that if she wanted to continue, she would have to turn on the porch light, so she went inside instead. The afternoon was sliding into evening anyway, and we all had things to check off our daily lists before we could finally go to bed. We ate dinner, we watched television, we sang to our children as they fell asleep. We washed the dishes, the clothes, our bodies. We lay down, we reached for our husbands. We did not discuss the man we saw. Why would we?

The next morning Alice didn’t wake up wondering about the man, but she thought of him as she brushed her teeth and looked at herself in the mirror. There he was in a corner of her brain, popping up amid calculus problems and the chapters of Huckleberry Finn she would be quizzed on and her plans for the afternoon—swimming in her backyard with Susannah Jenkins, and she was going to ask Susannah to undo the back clasp of her suit so she could tan her back; she knew, like we all did, she would be the homecoming queen tomorrow, and she wanted to be brown as a nut—and in her mind, the man looked different from how he did the day before. In her memory, he was tall and movie-star handsome, with a brilliant smile and an appealing, feral sort of quality around the eyes, like his eyes had teeth as well; the look they gave her as he lifted the camera up was sharp and hungry, but it was a ravenousness she liked. He appreciated her, that much was obvious. And though we did not know it then—then she was still our girl, our pretty Alice—she was beginning to feel the allure of a similar rapaciousness, the pull of being so hungry, how good it feels to want so much.

(We all know what it is to want. Not materially, maybe. Here we are well fed and well housed, well dressed, well groomed, and our children are well taken care of. Alice Lange was, too, no matter the stories you might hear now. When she came down the stairs that morning, she came down to breakfast: eggs, toast, glistening berries like rubies in a small glass bowl. What did she have to want? Like the rest of us, she had the entire world to want, but we’ve always known enough to stop the chase when there is something too big to lose, known when to bite down and stop the hunger that threatens to consume us.)

Downstairs, in the kitchen with the triangles of toast and sunny eggs, her mother read the newspaper. She looked up when she heard the slap of Alice’s feet on the stairs and smiled at her daughter, a marvel, the miracle of her person in the house they shared together. It was only the two of them, Alice’s father having died when the girl was

five. She barely remembered him; her mother remembered him every day. When she looked at Alice, she saw him there, too, resurrected in the deep blue of her eyes, in the foot she bounced while she read or studied, in the length of her legs. It was an exquisite sort of pain, to look at her girl.

“Hi, sweetheart,” her mother said. She nudged the plate of food across the table to the place at the seat across from her. On her own plate was half a piece of toast, buttered. “Eat,” she said.

Alice wore a satchel on her right shoulder, heavy with class books, and for a second it seemed she was going to shrug it off so she could sit and have breakfast with her mother, but just as the bag was slipping down her shoulder, she hitched it back in place. “I’m not hungry,” she said, but grabbed a handful of raspberries from the little glass bowl and popped one, then two into her mouth.

“What do you have going on today?” her mother asked. “Any tests?”

“A quiz,” said Alice. “Susannah is coming over after school. We’re going swimming.”

“That will be nice,” her mother said. “Anything else exciting happening?”

“No,” said Alice. She reached down and plucked the toast from the plate and nibbled it. “Well,” she said, “actually, someone took a picture of me. I’m curious to see how it turned out.” She laughed. “That’s not very exciting, though, is it?”

“Oh?” said her mother. “Who was it? Is there a photography class at school?”

Suddenly Alice didn’t know why she had told her mother in the first place. “Just someone at school,” she said.

“If it’s good,” her mother said, “maybe your friend can make a copy of it for me.”

Alice shoved the piece of toast in her mouth, pressed a stray crumb on her chin, scooted it to her lips. She swallowed the toast, said, “I better go.” She came around the table and kissed her mother’s cheek, her hand on her mother’s shoulder, her mother’s hand lightly on hers. Her mother’s fingertips were cool and soft.

“Be good,” her mother said. “I’ll make sure there are clean pool towels for you and Susannah.”

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves