- Home

- Alison Wisdom

We Can Only Save Ourselves Page 12

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Page 12

“You know,” said Bev, “I bet she wasn’t late at all. I bet she put them out last night after we went to bed. Just in the nick of time.”

“Oh, that somehow seems sadder,” April said. “I hope she put them out early this morning.”

In fact, some of us had seen her walking down the street at night carrying a basket, like a very grown-up Little Red Riding Hood. When Sweetie had begun barking around eleven, and Mrs. McEntyre forced herself to peek out the window, she saw Mrs. Lange retreating down her path. Mrs. McEntyre had lost a sister when she was a teenager, and truthfully, Alice Lange had always reminded her of that other girl. Both blond, big-eyed, forever eighteen. She considered opening the door to call after Mrs. Lange—What? Thank you? Hello? I’m sorry?—but in the end, she waited until her neighbor was out of sight to retrieve the bread.

The other person to see Mrs. Lange was Billy, who typically went to his window to watch the dark street as soon as his mother tucked him in and closed the door behind her. That evening, he spotted a woman stopping briefly at each house and leaving an offering, but he couldn’t see who it was, and thought she might be a ghost. Briefly, he considered being scared, but in the end decided not to be. He was safe in his room; here, he could observe her with the cool detachment of a scientist. He even made some notes about her in his journal. The next day after school, he told his mom about the ghost and showed her his written observations. That wasn’t a ghost, April said, it was only their neighbor Mrs. Lange, and when Billy walked into the other room to start on his homework, she got on the phone to tell Bev what she’d discovered.

Now it is October again, nearly a whole year since Alice left us forever. The air is a little cooler, and the leaves have dropped the same seeds Alice crushed beneath her thin sneakers as she hurried away from us. Some of the husbands sweep the sidewalks clear of them; some of our children gather the seeds in their open palms and carry them home, and we have to remind them not to bring them inside the house. Give them to the birds, the squirrels, we suggest, which pacifies the children. It makes them happy to think of feeding wild things who already know how to feed themselves. It feels like a gesture of kindness, even though we know it’s an unnecessary one.

On the first of the month, as if she couldn’t wait a day longer, Mrs. Lange brings us pumpkin bread. The bread is perfect. It is moist, soft, the right balance of dense and light, a perfect combination of nutmeg and ginger. Mrs. Lange, we say to her, you are an artist. What harm does it cause if we exaggerate, only a tad? Mrs. Lange is gracious and humble. She stops herself from saying, “It was always Alice who did the spices.” Alice, excellent at chemistry, too, could eyeball a tablespoon, a teaspoon, even a half a teaspoon. She would line the spice jars up like little soldiers, rank and file, and she could anticipate what her mother would need and when, even if she was doing her algebra homework or reading Pride and Prejudice as her mother bustled around.

It had always been for Mrs. Lange a world of two; other people passed through, but they were only visitors. She and Alice were the sole true inhabitants, and the world was the size of whatever space they occupied at the moment—when they baked, it was the size of the kitchen; when they slept each in her own bedroom every night, the world’s dimensions encompassed the house. Now, they are apart, and Mrs. Lange can’t picture where her daughter is, and so the size of the world is infinite. And yet, for Mrs. Lange, regardless of the endless depth and breadth of the world, the population remains at two.

Instead of telling us about Alice and how it felt to share a warm kitchen with her, she simply thanks us and moves along to her next stop, to our immense relief.

Three days later, on a Sunday, we come home from church to find baggies of snickerdoodles at our front doors. “Who are these from?” asks Billy, already opening one.

“Stop right there,” says April, thinking of all those years ago when she and Bev bonded over the poisoned pumpkin bread and the baby-stealing ring. “Just in case,” she says.

“They’re from Mrs. Lange,” says Eric. “Who else leaves baked goods for us?”

“I’m just going to ask her,” April says. “Don’t let Billy have a cookie.” She walks down the street to the Langes’ house and knocks on the door. No one answers. The front porch swing glides a little on the breeze. A cool front, April knows, is blowing in later today, and she shivers in anticipation. Behind her, a dog barks. She turns around and sees Mrs. McEntyre and Sweetie watching her. “Sweetie’s in everyone’s business,” Mrs. McEntyre says, even though now the dog has ducked her head and snuffles around the fallen seeds and leaves, and it is Mrs. McEntyre who looks at her. She takes note of April’s shoes—beige, sensible heels. “Did you just finish at church?” she asks April.

“I did, but now I’m hoping to find Mrs. Lange.”

“That sweet woman,” Mrs. McEntyre says, already planning on telling the rest of us how she’d caught April snooping around. “First pumpkin bread and now cookies. Imagine.”

April isn’t sure what, exactly, she is supposed to imagine, so she nods and turns back to the door. After a moment, Mrs. McEntyre and Sweetie continue on, and April hears Sweetie bark in the distance.

She knocks again and considers trying to peek in the windows, but the blinds are closed up tight, and so she waits another minute and leaves.

Once home, she calls Bev. “Did you get cookies?” she asks.

“Yes,” her friend says. “And we’ve all eaten one, and no one’s died yet.”

“That’s all I needed to know,” April says. She gives a thumbs-up to Billy, who is watching eagerly from the entryway to the kitchen, the plastic bag in his hand.

That night, April sits on the edge of the mattress as Eric gets ready for bed and tells him about the Lange house. “I hope she isn’t, you know,” says April.

“Dead?” asks Eric, dropping his pants to the floor.

“Fold those,” says April. “Yes. I always worry she might, I don’t know, you know what I mean.”

“Kill herself?”

“Aren’t you a little worried?” April asks. Eric folds his pants and sets them on a chair in the corner of the room. She sighs inwardly. How hard would it be to put them in a drawer?

“She’s lucky to have such nice neighbors concerned about her,” Eric says. “It really isn’t my business, but it’s nice to know other people are looking out for her.” He climbs into bed, and April slips in beside him.

“The cookies were good,” April says.

“They were,” says Eric. He rolls toward her. “Turn off the light,” he says, his voice low.

Two days later, muffins. A few days after that, loaves of heavy, beery bread. After that, there is nothing for a week, and then, unseasonably, sugar cookies with the duck fluff yellow sprinkles appear. We grow concerned. This is not normal behavior.

On the day the sugar cookies arrive, Bev, April, and Charlotte Price sit in front of April’s house watching the children ride their bikes up and down the street. The baby sits on Bev’s lap, the front of her gray dress wet with drool and her mother’s bent knuckle in her mouth. A plate of cookies like small yellow suns rests on the lawn in front of them, blades of grass sticking up around its perimeter. “We should have an intervention,” says Charlotte. “I love a cookie as much as anyone else, but honestly, this is too much.”

“I don’t mind it at all,” says April, and laughs. Her midsection is thicker than it’s ever been, and when she looks in the mirror, she sees the shape of her mother. But it worries her less than she would have thought it would; she likes, for example, the pleasant weight of her breasts, which have taken on a fullness they haven’t had since she nursed Billy. She also knows, though, that Charlotte Price, thin as a reed, would never understand because here you should constantly be striving to be something better than what you are. We are lucky to be here, where so many of our problems are solved, allowing us the energy and time to devote to other areas of our lives that need improvement.

“I worry about what it me

ans for Mrs. Lange,” says Bev. “April, I know you feel the same way.”

“Yes,” she says. “All this baking. When does she sleep?”

Charlotte looks out to the street where her twins are racing side by side, the other boys behind them. When they ride, the boys stand up on their bikes, legs straight, and the wind pushes their hair off their foreheads. “I’ll talk to her,” she says, her eyes still on the boys.

Bev widens her eyes at April, who cringes. “We could,” Bev says. “She’s always liked me. I can bring the baby. She might like that.” She props the baby up so she’s standing unsteadily on her chubby feet. “Those feet are like pillows,” Bev said last night to Todd. “How on earth can they be good for anything but nibbling?”

“I’ll go,” Charlotte says now, looking back to her. There is a glint in Charlotte’s eyes and a note in her voice that both say this matter is resolved and will not be discussed further.

“Maybe she’s right, Bev,” says April. “You should let Charlotte do it.”

Bev is surprised. She looks at her friend to see if there’s a wink stirring at the corner of her eye, a sign that April is simply placating Charlotte, who is known for steamrolling anyone who disagrees with her, but April only looks concerned.

“All right,” says Bev. “But I’m happy to go over there if you change your mind.”

“I promise it’ll be fine, Bev,” says Charlotte, leaning over to pat Bev on the hand, but Bev moves it at the last moment to dry the baby’s glistening chin.

A few houses down, a door slams, and the women all look up to see Christine Pittman bounding out of her house and waving at the boys.

“Christine!” Timmy calls, drawing out the last syllable of her name.

“I’m coming,” she says. “Hang on!” Her bike lies on the lawn, and she grabs it, hops on, and starts down the driveway.

Charlotte stands up and waves at the girl. “Christine,” she says. “Come here, say hello.” Dutifully, Christine changes course and rides up the driveway of Bev’s house. “Hi,” she says.

“Sit,” says Charlotte. “Join the girls.”

Christine glances over at the boys, who watched her glide down her driveway and now are pumping up April’s driveway and then speeding down, feet off the pedals. “Okay,” she says, and gently lays the bike down, the front wheel still spinning. “Am I in trouble?”

“No!” says Bev. “You can go play! We just wanted to say hi.”

“Sit,” says Charlotte again. “Where’s your mother?”

“Inside,” she says. “She said it was fine if I came out since you were all out here. She has a headache.”

“It won’t kill you to watch for a while,” Charlotte says. “The boys aren’t going anywhere.”

So Christine sits down with the women and together they watch the boys zoom by. At first, they yell for Christine each time they pass, but eventually they stop calling her name and start only hooting and waving, and the girls on the lawn wave back.

That night, Charlotte Price goes over and rings Mrs. Lange’s doorbell. Surprised by the unexpected visitor, Mrs. Lange lets Charlotte inside and leads her into the kitchen, which is warm and smells like Christmas. Gingerbread, says Mrs. Lange.

We’re worried about you, Charlotte says. All this baking. Please, Mrs. Lange, take a break.

Mrs. Lange says she doesn’t mind.

Please, Charlotte says again. We all feel very uncomfortable. She stands up and goes to the pantry, while Mrs. Lange takes a seat at the kitchen table, watches. Charlotte pulls out the bag of flour, a bag of sugar, a bottle of vanilla. She places them on the counter. A half-used bag of chocolate chips. A jar of molasses. Honey. This flour is old, Charlotte remarks.

It’s fine, says Mrs. Lange.

You can bake us the gingerbread cookies at Christmas, Charlotte tells her. The sugar cookies in the spring. She holds up a hand. No more than that. Charlotte picks up the bag of flour, the top of which has been curled over to keep it closed, walks over to the trash can, and drops it in. Then she takes the bottle of vanilla, checks that the lid is sealed tightly, and puts it in her purse. I’m out, she says. Thank you. You’ll feel better without all the extra work.

When Charlotte is gone, Mrs. Lange goes inside and takes the gingerbread from the oven. She places another batter-filled loaf pan inside. After it all cools, she slices it up and wraps it, making sure there’s a half loaf for every neighbor, until every surface in her kitchen is covered in tinfoil-wrapped stacks.

In the morning, we wake up to the packages on our doorstep. We eat it with our coffee, break off pieces with our fingers, place them in our mouths. We think of Mrs. Lange, and, always, of Alice.

Chapter Nineteen

THE NIGHT AFTER Wesley bought the priest’s robes, he told them it was time for a game. Alice wondered if it would be the same one they had played the night he’d placed the little tablets on their tongues—when Hannah Fay had cried and Wesley had slapped Janie. But it turned out Wesley loved games, had an entire head full of games he carried around with him, complete with rules, and the fear game was only one of them. “A new one,” he said to the girls as they rose to clear the plates after dinner. “I’m inspired.” He sat at the table as Alice and the others flitted around him, grabbing dishes and cups, running a damp rag across the table. He leaned against the back of the chair, which was pushed slightly away from the table, with his legs out straight and his feet bare.

“So what’s the game?” Hannah Fay asked him as she wiped down the stove, glancing over her shoulder. “Does it have anything to do with your new outfit?”

“Bingo,” he said, pointing at her.

“Do we all get to dress up?” asked Janie. She took the dish towel she was holding and draped it over her head and held it together at her chin like a nun’s habit.

“Sister Janie,” teased Hannah Fay. Apple came up behind Janie and yanked it away, but Janie just shook back her hair and laughed.

“It’s not a costume,” Wesley said. “It’s a sacred garment.”

“Tell us how to play, Wesley,” Alice said. “Are there rules?”

“Maybe game is the wrong word,” Wesley said thoughtfully. “Play is the wrong word. I’m thinking this is more like a practice. Or a discipline.”

“A sacrament,” said Kathryn. She sat down at the table beside him, and Hannah Fay took the chair on his other side.

Wesley clapped his hands together. “Yes,” he said. “Exactly. That’s what it is exactly. You know, I wasn’t entirely joking about starting my own religion.”

“So you’re saying eventually we’ll all call you Father,” Apple said. “Got it.”

“Who’s going first?” Alice asked quickly as she noticed Wesley’s body tense. “I can if you want.”

“I’m going to get dressed,” he said. “And then I’ll decide. Hannah Fay, we’ll use your room if that’s all right.”

“Of course,” she said. “It’s not really my room anyway.”

“It’s everyone’s room,” Kathryn said.

“It’s Hannah Fay’s room,” Apple said.

“I love you, Apple,” Hannah Fay said.

“I love you too,” said Apple.

“All right, calm down,” Wesley said. “We’ve got a sacrament to perform.”

Alice sat between Hannah Fay and Kathryn on the couch, and Apple and Janie took the floor. They all sat facing the study, whose French doors were closed, so they could see Wesley as soon as he emerged. During her first trimester, Hannah Fay had told Alice, she’d had terrible insomnia—any amount of light was enough to keep her awake—so Wesley had tacked blankets over the windowpanes on the doors. They were still in place, so no one could tell what he was doing, though Janie said he’d asked her where the extra candles were, the ones Kathryn insisted on keeping handy in case the power ever went out. Kathryn hadn’t grown up here, with all our sunshine, and when she was a kid on the Gulf coast, she’d told Alice, summer storms had wracked her family’s tiny house until

the electricity went out and they were plunged into darkness. (And this is how we imagine Kathryn’s mother, still in that rickety coastal cottage, the soil wet and shifting underneath, sitting, walking, sleeping in the dark.)

They were quiet as they waited for Wesley, and Alice remembered standing with Susannah and a line of other girls outside the locker room the summer before their freshman year, waiting to be called one by one into the room for the physical they needed in order to try out for the volleyball team. “I heard they give you a shot,” one girl said. “In your butt.”

“No way,” Susannah had said. “But Mary Mueller said they ask you if you’re a virgin.”

“What does that have to do with volleyball?” asked Alice, not one to be easily taken in, and no one could give her a real answer. In the end, when the door shut behind Alice and she faced the school nurse and Coach Timmons, all she had to do was inhale, exhale, touch her toes, stand on the scale, and rotate her hips, her neck, her wrists. Alice made the A team and got to play in the big gym before the varsity team played. Susannah and whoever said they were getting shots in the rear (it was Millie, forgettable, dependable Millie) made the B team, whose games were relegated to the practice gym, the one with no bleachers. Jealous, Susannah didn’t talk to Alice for a week, until eventually she couldn’t keep it up anymore, couldn’t stop herself from loving Alice Lange.

But this was the mood as the girls waited outside the study: excitement, tension, wonder. Who would they be required to be? Who would Wesley be? Father Wesley, Brother Wesley. Wesley in the cassock, Wesley in the shadows, Wesley in the light. The door opened, but he did not emerge. “Alice,” he said, though it wasn’t loud, maybe even a rung below the volume of his regular voice, and it seemed to her like the darkness of the study was calling her name. A disembodied voice, or maybe the voice came from the house, and the house was the body and the study its mouth, opening and summoning. Alice stood up. “When you come out, tell us what happens,” Apple said.

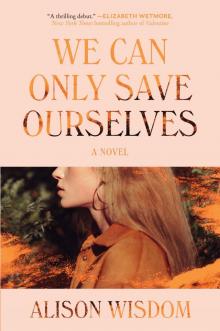

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves