- Home

- Alison Wisdom

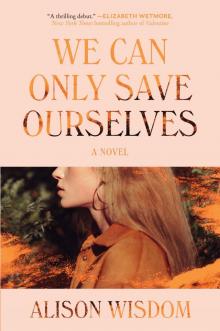

We Can Only Save Ourselves Page 24

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Page 24

“Good idea,” said Janie.

In the night, Alice heard Hannah Fay come out of her room, and Alice realized she herself had been sleeping. It happened so quickly—Hannah Fay opening the front door and slipping away—that for a second after she woke, Alice told herself it was too fast, she didn’t have time to stop her.

But she knew this was wrong; of course she could have stopped her. She could have leapt up from the couch and followed her out onto the porch, pleaded with her to stay. She knew that’s what Wesley would want her to do. She could close her eyes and feel Wesley directing her all the way from the desert, feel his voice in her throat, his bones under her skin, his muscles in her legs as she stood up to follow Hannah Fay. His hands in her hands to grab her, bring her back.

She loved Hannah Fay, but she could give Wesley a baby, too, and isn’t that what Wesley loved most about Hannah Fay? (Yes! He loves Hannah Fay because when he looks at her, he sees himself reflected back, as if that stomach of hers was a mirror and not a real flesh-and-blood thing, housing a beating heart and growing limbs, but something cold, the only life there the image of himself he sees. Men like Wesley, this is what they want above all—to look into a woman’s eyes and see only themselves reflected there.)

She could tell the others she fell asleep and that when she woke up, Hannah Fay’s room was empty, and they wouldn’t think anything but the best of her, that she had been vigilant but exhausted, and they wouldn’t know that Alice had simply let her go.

Chapter Thirty-Three

WESLEY AND KATHRYN came home the following afternoon, as the day was winding down and the light was gold, to find the girls assembled in the living room. They came into the house like lovers arriving home from a honeymoon. They’d only been in the desert for a day, but already Wesley’s skin was tanned even more deeply, and Kathryn sported freckles no one knew she was capable of conjuring.

“It’s magical,” Kathryn said as soon as they walked in. “You’ll love it.”

“The ranch itself leaves a little to be desired,” Wesley said, sliding his bag off his shoulder to the floor. “But all things considered, when you think about what’s going to happen everywhere else, it’s pretty damn good.” He scanned the room. “Is Hannah Fay napping?” he asked. “I want her to hear about this too. We’ll still need more money, but we made a deal. It’s good news.”

“Wesley,” Apple said, “she left.”

“Where’d she go?” he asked, his face darkening.

“We don’t know,” Janie said.

There was a long silence that stretched like a bridge between them. “But why?”

Alice watched Apple and Janie look at each other. She glanced over at Kathryn, who she realized had been watching her with a questioning look.

“She found out about your son,” Apple said. “And wife.”

Wesley bit his lip and squinted up at the ceiling, where the domed light glowed weakly, like a small, sad sun. “Motherfucker,” he said. “Apple. What the fuck? Why?” Kathryn put her hand on Wesley’s shoulder, but he shrugged it off, and she took a step back. “You are ruining everything,” he said. “Everything.”

“I thought she knew!” Apple said. “I’m sorry, Wesley. You have to believe me.” Janie took a step closer to Apple and slipped an arm around her waist as if to steady her.

“She is having my baby, Apple,” Wesley said through clenched teeth. “She is having my baby any day now. And now she is gone, out wandering around a world full of people who want to kill her.”

“They don’t want to kill her,” Apple said. “No one would kill a pregnant woman. Besides, the world isn’t as dangerous as you say it is.”

Wesley laughed. “That’s certainly a change in attitude from the other night.” He made his voice higher pitched, frightened. “‘Please, Wesley, no. What if the man who picks me up kills me?’”

Apple’s cheeks flushed. “I’m sorry.”

Wesley put his hands on his hips and leaned his head back, exhaling. Kathryn tried to put her hand on his shoulder again, and this time he let her. “Okay,” he said. “She’ll come back. I know she will. I will bring her back.”

“Are you—” Kathryn started. “Are you going to—do anything else?”

“Wouldn’t you like that, Kathryn?” Apple said. “If he punished me?”

“No, actually, I would not. God, Apple.”

“I’m not doing anything else yet,” Wesley said. “Apple, I know you would never hurt Hannah Fay intentionally. I believe it was an accident but a very unfortunate one, and of course there will be consequences. I just don’t have the capacity for dealing with them right now. My focus is on Hannah Fay and our baby.”

“I understand,” Apple said softly. Beside her, Janie squeezed her waist. Alice said nothing.

“I need to shower,” Wesley said. He started down the hall, and Kathryn followed after him, but he stopped suddenly and turned around to face the others, nearly colliding with her. “Apple,” he said, and she looked up. “I assume you’ve told the others about your own child you left.”

“Yes,” she said.

He nodded and went into Kathryn’s room. Soon they heard the sound of running water.

“I told you,” Apple said to Alice, and then Apple turned and left too. Janie went after her, and Alice was all alone.

(We have a guess as to why Wesley skipped Hannah Fay the night of the confessions, why he burned the cassock: the game had to end. It was an oversight, he said, though we think it’s possible he realized that Hannah Fay, the gentlest of his girls, would receive none of his confessions well, and she would leave, and his child would be lost to him. This would be the worst thing to happen. Apple saw that too. It had been a good idea in theory, to share secrets with them, create the illusion that they were in a partnership that, yes, went five ways, but also existed between two imperfect people, flawed but good, and it was only when it came to Hannah Fay’s turn that Wesley could see he had run a terrible risk. What if they left? What if he realized his grip on them wasn’t as tight as he had thought? That last worry—we know how that feels, we who have lost Alice Lange.

But anyway, this is why he got rid of the cassock.

And why burn it? Wesley is the kind of man who loves a spectacle. We’ve seen it, Alice has too. We have a feeling that wherever he is now, it will only get worse.)

That night, Wesley asked Alice to sleep outside with him. They lay on a blanket, another blanket on top of them. When they had sex, Alice knew her primary role was the comforter, the pleaser, the secondary role to be pleased herself.

“Everything is so fucked,” he said after.

“I know it feels that way,” Alice began, but Wesley was already shaking his head.

“It is,” he said. “Trust me. We need to get out of here soon.”

“We will!” said Alice. “Tell me more about the ranch.” She rolled over on her side to face him, but he stayed on his back, like he was looking at the stars, though the night sky was clouded over.

“It’s primitive. I mean, we’ll be able to cook and take showers, but they might not be hot.”

“That’s okay!” Alice said in what she hoped was a bright tone. “We don’t mind roughing it.”

“Like I said, considering that everything else will be essentially gone, this isn’t a bad deal at all,” he said.

“So we’ll just go out there and wait?” Alice asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “Can I be honest with you?”

“Of course. Always.”

“I’m so discouraged. We still need money, even with the guy cutting us a break. More than what we have. It was a stretch even before Apple—” He shook his head. “And now Hannah Fay is gone.” He closed his eyes. Alice sat up and moved even closer to him, began to stroke his hair with her hand.

“She’ll be back,” she said.

Wesley said nothing but rearranged himself, putting his head in her lap. Neither of them said anything else, and when he drifted off, Alice gently lift

ed his head and lay beside him, like they were two spoons, and she fell asleep like that too. When she woke up, though, they were apart. Either he had rolled away from her, or she from him—she wasn’t sure.

Wesley was gone most of the day, looking for Hannah Fay, he said. But when he returned for dinner alone, he didn’t say anything. No one asked him any questions.

After dinner, Janie went to take a shower, and the others all moved instinctively to the front porch. Alice wondered if it was so they could watch for Hannah Fay, see her as soon as she arrived home. Tonight, the stars were bright, but everything on earth felt somber to Alice. She wanted to fix it. “I have an announcement,” she said. The girls looked at her, then to Wesley.

“Go ahead,” Wesley said.

“I can get money,” Alice said. “Probably not all we need, but some.”

“Finally,” Apple said. “You’re going to start stripping.”

“My mom keeps cash in the house,” Alice said, ignoring her. “I took some when I left but not all. I could go home, and I bet I could get it.”

Wesley leaned toward her.

“How much?” he asked. “I don’t think we should steal it. I want us to be honest in our dealings.”

“I’ll ask for it,” she said. She sat against the wall of the house closest to the door. Behind her, she could feel the thrum of the water running through the pipes for Janie’s shower. “I can pull it off. Wesley, can you drive me tomorrow?”

“No can do,” said Wesley. “You’ll have to take the bus. I have business here in the morning.”

“That’s fine,” said Alice, though she had been hoping for another road trip, had even pictured herself introducing Wesley to her mother. But the bus would be fine too. She could stay for a few days, could get some more clothes for the girls, and the money, and then she would come back here. Then they would leave for the desert.

“One thing, though. Don’t mention me,” Wesley said now to Alice. “To your mother, to anyone. Don’t tell them my name.”

“Why?” asked Alice.

“They don’t deserve to know it,” he said. “You know names are a gift.”

Across from him, Apple coughed. “What now, Apple,” Wesley said.

“Nothing,” she said. “Sorry. I just need some water.”

Wesley turned back to Alice. “All right. Get the money, say good-bye. You won’t see your mother again when we go to the desert. So do what you need to do.”

“Okay,” said Alice. “But the only thing I need to do there is get the money.”

“One condition, though, if you do,” he said. “Come back. You have to come back.”

“Of course I will,” Alice said. “Don’t worry.”

“Remember where the love is,” Wesley said. “It’s only here. Nowhere else. I’ll know if you’re thinking of staying.”

“I won’t be,” said Alice. “But it’s nice to know I’ll be missed.”

“I’ll take you to the bus in the morning,” he said. “I’m sleeping alone tonight. Kathryn, you can sleep in Hannah Fay’s room since it’s empty.”

Then he stood up and went inside, leaving the girls alone on the front porch. They sat there silently and then Kathryn got up and went inside, too, without saying good night.

Apple sat with her heels together and knees up, her legs open like the waiting mouth of a bear trap.

“Are you okay?” Alice asked her.

She tipped her head forward. “Yeah. I’m just tired of him being a fucking jerk, not saying what he means.”

“I don’t think that’s true,” Alice said. “Besides, you’re hardly one to talk.”

“When he said he doesn’t want you to say his name to your mom—that’s not about his true name stuff. He just doesn’t want to get busted for anything if you get caught.”

“So what?” asked Alice. “We have to protect him.”

“Everything’s a game to him,” Apple said. “How can you not see that?”

“How can you say that? Look how he’s been searching for Hannah Fay. He’s serious. And he still cares about you,” she said. “Even after what you’ve done. He cares about all of us. That’s why we’re here.”

“After what I’ve done?” Apple laughed. “Oh please. Now look who’s talking.”

“I apologized,” Alice said stiffly. But suddenly she wasn’t sure if she had. Or if she should.

“For which thing?” Apple asked. Alice didn’t respond.

“That first night,” Apple said. She rearranged herself so her legs were folded underneath her. “I bet he took you to that library. He had Kathryn’s keys, and he took you to the library and pointed out the window to all the lights and said some romantic bullshit and then fucked you standing up, and it was all passionate and intense, and you probably didn’t come, but you got off on it in other ways, so you told yourself you didn’t care.” She pointed at Alice, thrusting a finger toward her chest, stopping just short of touching her. “Tell me I’m wrong,” she said. “But I bet you can’t.”

They hadn’t looked out the window. The curtains had been pulled back, there had been lights in the distance—Alice could remember thinking they looked like candles burning—but he had showed her the books. She had touched their spines. Those were the last books she’d touched. It was strange not to have any books for months, just those magazines, old and crumbling. “No,” said Alice. “You’re wrong. Sorry.”

“I bet I’m close,” Apple said. She tucked her hair behind her ears, which made her face look sharper, her cheekbones higher. “You don’t have to tell me if you don’t want to,” she said. “I’m just saying I know more than you do.”

“You are so mean,” Alice said. “I mean, God. Why don’t you leave if he’s so awful?”

“Like I said,” Apple said. “I know more than you do. And besides, not all of us have fancy houses to go back to.”

“Tell me what I don’t know, then,” said Alice. “If it’s so important.”

“He isn’t who you think,” Apple said. “And you know what? His photographs aren’t that good. Anyone could take them. And his paintings are worse. Have you ever noticed he doesn’t paint actual people?” She leaned closer and lowered her voice, like she was revealing a secret. “It’s because he doesn’t know how.”

“They’re abstract,” said Alice.

“He left his own child,” Apple said.

“So did you!”

“That was a very different circumstance, and you know it,” Apple said.

Alice did know it. “Okay,” she said gently. “I know. I’ll see you when I get back.”

“You know I’ll be here,” Apple said. “I bet you’ll cry when you see your mom.” She held her hand over her heart. “Mother and daughter reunited. A Christmas miracle.”

Alice pushed herself up, brushing off the seat of her pants. When she got to the door, she paused and turned back to Apple. “What does your name mean?” she asked.

“That’s something I only share with Wesley,” Apple said. “Sorry. Some things are private.”

The next morning, Kathryn drove Alice to the bus stop and waved her off with little sentimentality, though Alice felt a sting in her heart as she said good-bye, even though it was only Kathryn in the car, even though she would be gone only briefly. On the bus, she watched the sun come up through the little square of window over her seat. At the bus station near home, she called her mother. She answered on the first ring, and she sounded the same to Alice. She said hello and heard her mother breathe in. “Angel,” her mother said, and Alice began to cry.

Chapter Thirty-Four

HERE IS WHAT we saw: Mrs. Lange’s sedan backing out of the driveway, a practical car, a car for a mother but the color of champagne, like the shade of paint was the one place where she could afford to be frivolous. It was a Saturday, and she wore a simple dress with a big cardigan flapping open over it. When she rushed out of the house, her legs were bare, and though Mrs. McEntyre noted that Mrs. Lange’s flats were either nav

y blue or black, she couldn’t say exactly.

Here is what else we saw: when Mrs. Lange returned, she didn’t pull her car back into her garage but stopped outside of it. We could see she wasn’t alone, but the two figures we spotted in the car were so still that we would have thought it was empty, because who would just sit in there for that long? Then we saw the driver’s-side door open, Mrs. Lange stepping out. Another open door. Alice Lange, even slimmer than she was when she left. We could have held her in our hands, slipped her into our pockets. Hair long and unbrushed but still as bright as a gold coin. Wearing unfamiliar clothes.

Her shoes, Mrs. McEntyre would tell us later in a hopeful, breathless report, were the same: slender white tennis shoes. Her feet always looked so tiny in them. They still did.

Mrs. Lange must have wanted us to see her prodigal daughter, our girl now returned. This is the only explanation for why she parked her car outside the garage. We knew that she would have given anything to keep Alice there in her car, in her house, under the joyful hand she used to hold Alice’s fragile one. Her child was so thin now, with no mother to care for her. She held that bird-boned hand and let her imagination take her through Alice’s time away.

That’s how she hoped they would refer to this part of Alice’s life, her time away, like her quick stint at a summer camp, or a tour of Paris, Munich, London, a barefooted pilgrimage through the mountains of Spain. Alice’s time away was over and now her real life, her life here, could continue.

Alice did not plan to stay long, and she did intend to inform her mother of this fact, perhaps saying, “I’m only staying a night, maybe two, and then I’m going back, and we’re going to the desert, and I love you, and I hope you will stay safe. Maybe someday I’ll see you again.”

She wouldn’t tell her what she hoped she would stay safe from because she didn’t know herself. She knew there would be destruction—the earth shaking, seas rising, war breaking out—and then rebirth, but besides that, nothing. She would have liked to explain the little she knew, but her mother, for as much as Alice loved her, was still blind. How strange, Alice thought, to spend your whole life believing your mother knew best, knew more, and then suddenly the roles were reversed: you were the wise one, you were the one who understood the ways of the world.

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves