- Home

- Alison Wisdom

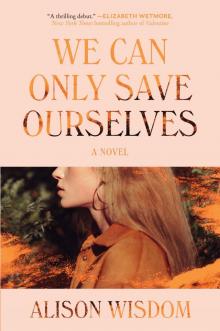

We Can Only Save Ourselves Page 6

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Page 6

“God, no,” said Wesley. “Stay right there. The light. Look up.”

Alice looked up, and a spear of light steeling in through the window shocked her eyes, but she lifted her chin until her eyes were in the shadow. This time, she let herself smile.

“A new muse?” asked a girl.

“Sadie,” Wesley said. Alice’s face burned; he had forgotten her name. Or maybe he had given her a new one already. Sadie Sadie Sadie. She imagined herself answering to it.

“I don’t go by that anymore,” the girl said.

“Too bad,” said Wesley. “It suited you. This is Alice.”

The girl turned to look at her. She looked to be a few years older than Alice, and wore her hair piled high on top of her head and heavy earrings that tugged and elongated her earlobes. Her lipstick was red, and when she smiled, Alice had the sensation of being bitten. “Hello,” the girl said.

“Hello,” said Alice, but Wesley put his arm around her waist and pulled her away.

“Let’s go outside,” Wesley said, then called over his shoulder, “Good-bye, Sadie.”

“Everyone here wants you,” Alice said as they stepped into the backyard. Wesley waved at people and said hello to the ones who approached him, but he didn’t stop to talk. He led Alice to the corner of the yard, a quiet place, away from the party. Someone jumped in the pool. Everyone cheered.

“They want me to take their picture,” he said. “There’s a difference. Everyone wants to see themselves how someone else sees them.”

“Not me,” said Alice. “I’m tired of seeing myself how other people see me.”

“I know,” said Wesley. “That’s why I’m so attracted to you.” He opened up his camera bag and pulled out a joint and a lighter. “Does this bother you?” he asked, holding it up between two pinched fingers.

“No,” said Alice truthfully. (We aren’t naïve. She was popular and friends with everyone. Besides, haven’t we conducted various experiments at our parties, with our friends, in hotel rooms with our husbands? What’s offensive is that the experience is wasted on the young, because really, what do they need to escape?)

“Good,” he said. “I don’t like prudes.”

“Good thing I’m not one, then,” Alice said, and they grinned at each other. He passed her the joint, and she took a hit, and they passed it back and forth and then to two others who came to join them, more strangers. But soon, Wesley said to them to just take it with them and go. “We want to be alone,” he said. But as they walked away, he took their picture.

“I hate these fucking people,” he said.

“Why?” asked Alice. It was night now, full fledged, dark blue, the paper lanterns like bright, glowing birds flying south for the winter. “Did you fuck that other girl too? Sadie.”

He looked at Alice, blue eyes intense and hot. A man, not a boy like sweet Ben Austin or even like Carl Miller, and she wanted to reach out and touch him, reach beneath his shirt and feel the skin there. She tried to see him the way other people saw him, the man who could make their ordinary faces and bodies into art, into something eternal. But looking at him, she thought oh, how wrong they were. He himself was the eternal thing they sought. She scooted herself closer to him.

“I will never lie to you,” he said.

“So you did,” Alice said.

He nodded. “But she wasn’t right,” he said. “She couldn’t see. You can see, though. Can’t you? I don’t want to be wrong again.”

“Yes,” said Alice.

He leaned toward her, and she leaned toward him and closed her eyes, ready to be kissed. Instead, he simply pressed his forehead against hers. She listened to his breathing, slowing hers to match it. His shirt was untucked from his jeans, and she touched its hem before she let her hand creep up and under to touch his skin. He flinched for a moment, as if her hand were cold, and she began to draw back when he trapped her hand with his, his on top of his shirt, hers underneath it, the thin fabric between them. He crawled his hand up her shirt, and she let his hand explore that hidden part of her body, and she shivered. “You and me,” he said softly. “We aren’t like these people. We see things they don’t.”

“How do you know?” she asked.

“Come on,” he said. “We’re at this party. Let’s have some fun.” He jumped up to his feet and pulled Alice with him, and she followed him, eating and drinking whatever he gave her—thick-skinned black olives, an oyster raw and cold, slipping down her throat, a flute of champagne she dropped when someone bumped into her; everyone cheered, and no one cleaned up the glass, which sparkled on the ground like ice. She smoked whatever he passed to her, too, until the night became a dream. The bright clothes of the girls looked like sunbursts, birds of paradise, slices of tropical fruit. Someone spilled red wine on Wesley’s shirt, and he peeled it off and disappeared inside the house. While he was gone, Alice felt the party outside began to sag, that the conversations happening in his absence were all focused on ways to say his name, as if mentioning him would cause him to materialize. The man with the camera, who is he? Wesley. I know him, he took my picture. He brought me here, Alice said proudly. Lucky girl. Eyebrows raised. This was a thing about Wesley, Alice could already see; people looked at her and wondered who she was, what was special about her. Alice had noticed herself wondering the same thing when she watched him talk to other party guests. If he would give a piece of himself to these people, they must be worth it. Though he was nowhere in sight, she felt him inside her, expanding and taking up room in her heart, lungs, stomach. He emerged a few minutes later in only a long white tunic that went past his knees, and Alice said his name, just to hear it. “You look like Jesus,” she said, touching his beard. She touched the lines around his mouth when he smiled, too, parentheses that separated his cheeks from the rest of his face.

“Maybe I am,” he said. He grabbed her hand and twirled her. She wished she were wearing a skirt that spun out like flower petals.

Later Wesley ended up with the guitar the man in the living room had been playing poorly, and he sat on the edge of a pool chair and played and sang, and Alice was delighted. Even his fingers and hands were lovely to her. “Is there anything you can’t do?” she asked.

“Math,” he said, and Alice laughed.

“It’s okay,” she said. “I’ve always been good with numbers, so if you ever need someone to calculate anything, I’m your girl.”

“My girl, huh?” Wesley said, grinning. Alice almost felt embarrassed, but she pushed that feeling away, emboldened by the drugs pumping through her body and the night air and the beautiful people everywhere and the company of Wesley. Already he was changing her, making her better, braver.

Wesley picked up his camera. “Watch this,” he said. “It’s like magic.” He stood up and pointed his camera at a couple sitting on the edge of the pool, their feet in the water and heads close together. “Hey,” Wesley called, and they turned around, ready, Alice could see, to be annoyed, but when they saw it was Wesley, they smiled. The woman leaned into the man; the man put his arm around her, and she looked up at him in an admiring way, eyes wide under thick lashes, lips parted. But from where she stood, Alice could see what the man with his feet in the pool could not—maybe the woman with him truly did love him, but in this moment, she was role-playing a woman in love. I am in love, the woman was saying, and this is how I show it. This is how I want it to be reflected.

Around them people posed and blinked at the flash of the camera in the dark, turning their faces away. “It’s good,” he said. “To have them flinching, looking away in the photos.” Alice loved to watch him turn his camera on them; it seemed to her that they gave him so little, and he took those paltry offerings and transformed them into something profound.

Wesley and Alice ended up in the pool, the Jesus tunic see-through and plastered to his body, Alice only in her bra and underwear. She shivered in the cool night air when they got out. Someone wrapped them in a towel and pushed them inside the house, Alice slipping a

little on the tile floor, and in what she supposed was a guest room, Wesley found his original clothes, the shirt with the red wine stain. He had somehow remembered to grab her jeans and shirt from beside the pool, and she peeled off her wet undergarments, thinking of the nude woman on the couch. She had made her body a work of art for the public to consume, and Alice could do the same, but only for Wesley. He picked her up and dropped her, laughing, on the bed, and she expected that then they would make love, but instead he took her feet and slid them into the jeans. He shimmied them up her body. He buttoned them. He sat her up and pulled her shirt on over her head. He turned out the lights. He climbed into bed next to her. Alice waited, breathless.

“Let’s get some sleep,” he said. “Tomorrow everything begins.”

Alice stared at the ceiling and felt grateful for the dark because her face grew hot. She told herself not to feel hurt that he didn’t seem to want her because surely he did, she was the one we all wanted, and she needed to trust that he had a plan. “You didn’t ever tell me why you hate those people,” she said.

In the dark, he sighed. “They’re not living in the now,” he said. “Do you know what I mean? They’re always thinking about the past or the future. When they let me take their picture, I can see them thinking about how one day in the future, they’ll look back at this moment, taken in the past, saved for the future. But they’re never really seeing anything. They’re not here in the now. They won’t let themselves feel anything. They’re blind people.”

Alice thought about this. She thought about the couple with their feet in the pool. The woman on the couch, Sadie with the red lips. She thought about herself, and then she thought about us, too, how we had shaped her. “Maybe it isn’t their fault,” she said. “Maybe it’s the world’s fault.”

“Someday,” said Wesley, “the world is going to burn, and I’m going to let it.”

“Don’t let me burn with it,” Alice said flippantly. She was beginning to get sleepy.

“Never,” Wesley said.

A sign, Alice thought, the fire, and then sleep pulled her under while outside the party burned on, its own kind of fire. (Miles away, we wondered what had become of Alice Lange, and her mother, alone in the house she had shared with her husband and then with her daughter and now with no one, wept until her insides felt empty, as though there were a fire within her, too, burning her from the inside out until everything was gone, an unquenchable flame her longing could never put out.)

When Alice awoke, disoriented and with an aching head, late morning light was streaming in through a window. Wesley was not in the room with her. Her bra and panties, which had been lying on the floor, were still damp, and she folded them both and tucked them into the crease of her underarm. She crossed her arms over her chest to hide her nipples, which she knew would be visible under her shirt, and stepped out of the room to look for Wesley.

She found him alone in the kitchen, eating a banana. “Where is everyone?” Alice asked.

“Oh, they’re in the various parts of the house,” he said. “And outside passed out on the grass. We were lucky we snagged a room. Do you want a banana?”

“Yes,” said Alice, thinking, truly, for the first time of her mother, the glistening eggs, the berries in the crystal bowl. What was her mother eating? Was she worried about Alice? (Nothing. Yes.)

“What’s under your arm?” asked Wesley.

“Oh,” said Alice. She pulled out the small pink square of her panties and the folded-over bra and put them on the kitchen counter. Wesley laughed. “They’re still wet,” she said.

“That’s the sign of a good night,” he said. “Any night you end up swimming in your underwear is a good one.”

Before this moment, as she’d wandered through the house looking for Wesley, Alice had prepared herself to find a diminished version of him, one that was not as handsome, not as clever, not as magical as the man whose image she was carrying in her head. She had told herself that maybe she would ask him for a ride to the bus station, and they would part ways. They had shared a perfect night, and that would be the end of it. What could be more sophisticated, more grown-up than that? But now, encountering him again, the man of him, the hunger in his light eyes and white teeth, Alice knew she would go anywhere with him. She walked over to him, took the half-eaten banana out of his hand, and kissed him. His hands tangled in her hair as he kissed her back. He smelled like chlorine, a scent she had always loved because it reminded her of sunshine, summertime, and then beneath that there was a heavier and warmer scent, like something that didn’t exist in any physical form and only emanated from this one specific person. This, she thought, was the way Wesley smelled. It made her giddy. When he pulled back, he grinned. “Let’s get the fuck out of here,” he said. “You can bring your banana with you.”

Outside, the air was cool. A man in running clothes jogged by. A woman was parking her car in the driveway across the street. How could anyone be doing anything so ordinary, Alice thought, when a person like Wesley existed in the world? “Wait,” Alice said, “shouldn’t we thank the host? Or tell him good-bye?”

“The host?” Wesley asked, unlocking the door to his truck and swinging it open. “I don’t even know whose house this is.” He cranked the window down and slapped the side of the truck. “Let’s go,” he said.

Alice ran around to the other side and slid herself in. There sat her bag, safe and sound, and the photo where she’d left it on the dashboard, her eyes staring straight up at the roof of the truck.

“Let’s go, then,” she said.

Chapter Nine

THEY STOPPED FOR burgers and fries, and Wesley got a milkshake, and he took pictures of Alice drinking it. After lunch, he pulled up beside a park in a hamlet outside the city, and Alice thought maybe he would photograph her there, too, so she lingered beside beautiful things until Wesley grabbed her by the wrist—not too hard, just enough to make her pay attention—and said, “Don’t.” Alice’s stomach turned, but she said nothing in response. She remembered the couple at the pool with their feet in the water, how the woman’s true, natural self had become hidden behind the artifice Wesley’s camera created. She vowed to herself she would not do that again. She would be authentic, the way Wesley liked her. Hadn’t she enough of posturing and posing? Hadn’t she left that behind with us?

So they walked in the park, down shadowy, lonely paths and talked—or Alice talked, and Wesley kept his eyes on her and listened, all about her life, what it had been and what she longed for it to be, about the fire she’d started. “A metaphor,” said Wesley.

“No,” she said. “A real one.” He raised his eyebrows and laughed long and loud when Alice nodded.

“Tell me all about that,” he said, so she did.

Finally, they drove long enough that Alice began to wonder if they were ever going home, to Wesley’s home, but then he said, “We’re not far from the house now. I just wanted to enjoy you and for you to enjoy me, and I felt like I needed to stop here, for a little while. But we’re almost there.”

They passed the university where Alice’s mother had encouraged her to apply. The streets they turned down to get there were narrow, with cars parked tightly on each side so that the truck had to slow to a creep, as though it were sucking itself in, making itself smaller to squeeze through.

Alice never wanted to go to this school. It felt too expected, too predictable for a girl like her. The trees that grew up next to the buildings were too much like the ones that shaded our yards, our sidewalks; the smell of the air, the feel of it on her shoulders and her face—that, too, was familiar. “Do you go to school here?” she asked. She realized that she didn’t know how old he was.

(Those of us who had seen him on our street in his boots, with his beard, the green canvas jacket, we would have told her that he was thirty, if he was a day.)

“Definitely not,” Wesley said. “I’m not an institution kind of guy, if you know what I mean.”

“Yeah,” said Alice, “

I do.” But she had always pictured herself in one institution after another: school, more school. Marriage, too, she imagined Wesley pointing out. That was an institution, wasn’t it? But those were prisons, weren’t they? Just ways to define people, borders to keep them locked in, trapped.

(Not trapped, we would tell her. Safe.)

“But we aren’t going here,” said Wesley. “Where we’re going is close by.”

They turned a corner, and Alice could see the campus now, unfolding like a page from a pop-up book, its buildings like fairy-tale castles with red roofs instead of turrets. Instead of stacked gray stones, their walls were smooth and white as pearls, as bones. “Pretty,” Alice said. Wesley had told her to roll down her window, and she stuck out a hand now, like she could shrink the buildings down into dormitories and cafés and libraries and hold them in her palm, create a tiny world to rule. A sorcerer, a magic girl. “Is it your house we’re going to later?” she asked Wesley.

“Sort of.”

“Roommates?” Alice asked.

“Sort of,” he said again.

(All kinds of gentlemen have brought us home in our day. Nice ones, bad ones, handsome ones, ugly ones. We’ve slept with them, we’ve slept beside them. We’ve left their houses early in the morning and called it nighttime so that we could tell our sisters and roommates of our own that we did not sleep over. But now when the gentlemen bring us home, they bring us home as wives. Their homes are our homes too. We sleep beneath our quilts, the ones our mothers bought us as wedding gifts. When we wake there now in the darkness of morning, we know where the bathroom is, where the switch is for the lamp on the bedside table. We do not hesitate to turn it on because we aren’t worried about waking up our men, not anymore, because we know them. It is a navigable land. The terrain is easy. Our bodies know it well. It is a wonderful thing to know and to be known.)

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves