- Home

- Alison Wisdom

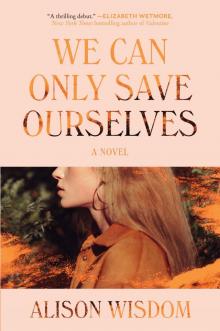

We Can Only Save Ourselves Page 9

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Page 9

“That’s what she says now,” Bev tells April. This is long after Alice has gone, after we know who has taken her away. “But at the time, do you remember how she went on and on?”

“‘Sweetie always barks!’” says April, in a terrible, nasally impression of Mrs. McEntyre that makes Bev giggle. “‘He’s a good boy, but you know he’s mouthy. Too mouthy for his own good.’”

“‘But he didn’t bark at the man,’” says Bev. “‘He may be mouthy, but he’s a good judge of character.’”

April laughs. “Eric wants to poison him,” she says.

“The man?” asks Bev. “Is he back?”

“No,” says April. “He wants to poison Sweetie.” She cocks her head to the side, thinking. “Maybe he wants to poison the man too. I’ve never asked.”

They are at Bev’s house. When Bev called earlier in the evening to invite April over, Eric still wasn’t home, and April was worried about leaving Billy, who was asleep in his room. “He won’t think you left him,” Bev had said. “Or he’ll know you’re over here, but he probably won’t even wake up before you’re home. Just come over now.”

“It isn’t right,” said April. “It isn’t safe for him to be alone.” She had paused then, and Bev had said her name, wondering if the line had gone out. Then came April again: “I hope you aren’t leaving the children alone either, Bevvy.”

Bev had laughed. “Where would I even be going?”

And now Eric is home and April is here, sitting and having a drink at Bev’s kitchen table. All the children are being properly watched now, tended to and listened for.

April watches Bev, who’s running rings around the bottom of the wineglass with her finger. “Do you want him to come back?” she asks. “The man.”

“No,” says Bev, looking back up to April. “Why would I?”

“I don’t know,” says April. “You just seemed interested. Overly interested.”

“Of course I’m interested,” she says. “It’s like a television show or a movie.”

“You’re bored?” asks April. “But you have the baby.”

“Exactly,” says Bev.

When April gets home that night, she can’t resist going upstairs to peek at Billy in his bed. His blanket has pictures of planets printed on it—there’s Jupiter near his feet, Earth curving underneath his body, disappearing.

Before she goes to bed, she calls Bev. “Listen,” she says when Bev answers. “I was only joking about Eric poisoning Sweetie. He would never really do it.”

“I know,” says Bev. “I can hardly even fathom the possibility.”

“Good,” says April. “I just didn’t want anyone to get the wrong impression of me. Or of Eric. You know.”

“I do,” says Bev, laughing. “My impression of you is very positive. Don’t worry.”

“Thank you,” says April in a serious voice, and Bev waits for April to laugh, too, to indicate that she’s in on the joke. She’s the one who raised the topic, after all! But then she only says, “Good night, Bevvy.”

“Good night,” says Bev, frowning at the phone as she hangs it up, and the lights of two lamps in two houses blink out.

Chapter Fifteen

KATHRYN HAD BEEN the first. She had met Wesley at an open mic night at, of all places, the university. “I thought you didn’t do institutions,” Alice joked to Wesley when Kathryn recounted the story. Alice had been here two full days, the longest she’d ever been away from her mother, except for the summer she went to camp for a week. There she had proved to be an excellent archer, and she wrote to her mother every day because she was worried if she didn’t, her mother might forget who she was and begin a whole new life without the burden of a daughter. (She wouldn’t, of course. We couldn’t. Our hearts, our bones, the blood running through our bodies—we could never live without those things either.)

“It was for the sake of art,” Wesley answered stiffly. “We make all kinds of sacrifices for our art.”

“Oh,” said Alice, looking at the other girls sitting around the living room. She wondered where their artistic talents lay, what they used their bodies to create. She knew they all modeled for Wesley. The photos were pinned to the walls with thumbtacks in every room: Kathryn at the library, behind a student asleep at one of the carrels; an earlier version of Janie, thinner, with something unclean about her, in a crowd of other dirty faces, dirty bodies. Hannah Fay outside somewhere, laughing, a piece of hair blown across her face and an orchard behind her. A picture of Apple, looking angry and sharply beautiful, holding a sleeping baby. Alice had asked Janie who the baby belonged to, and she said it was the baby of a woman Wesley knew; the girls, to bring in extra income for the household, sometimes babysat for her. “Apple hates babysitting, though,” Janie said. “She said she’d rather give a stranger a blow job.” Alice had laughed because Janie did, but she was (to our great relief) shocked to imagine performing that act for money, and beyond that, to prefer it to babysitting.

But the girls were never in the paintings. “Not that you can recognize, maybe,” Wesley had said. “But if you know what to look for, you’ll see them. You’ll see yourself too. You’ll see the truth.”

“Everyone here’s an artist?” Alice asked now. She considered herself. Perhaps Wesley looked at her and saw a latent ability in her, but Wesley said no, of course not.

“They appreciate art,” he said. “They’re not artists.”

They were in the living room, and it seemed like there were girls everywhere, one curled up in a chair, another sitting on an oversized floor cushion and picking dry cereal out of a chipped bowl, a third opening the blinds so that they all could watch the last light of the day drain away.

The past two nights she’d spent outside with Wesley, and she was exhausted because she had never really slept—instead, in a dreamlike state, she found herself reaching for him in the night, finding parts of his body she wanted to touch. She thought she remembered that at one point last night, Wesley put a gentle hand on her hip bone, stilling her and saying, “I’ll be here tomorrow. We both will. Now close your eyes.” She remembered him laughing softly, in a kind way, like he was amused by her, pleased with her, and then there was nothing. She must have fallen asleep. She thought of what Kathryn had told her on the first night, about him staying in her room, in her bed. About all the girls who liked him. But Alice was special among the girls, she could tell. A favorite. And why wouldn’t she be?

Now they all lounged in the living room, draped across the sofa and chairs and on the floor like silk shirts, like camisoles, like pantyhose and lingerie taken off by a lover and then left untouched. The front door was closed, but the back door was open, all that green like a secret the night was keeping, those vines and leaves and overgrown hedges growing unseen in the darkness. Keep the people out, the house seemed to say, the doors like mouths: let the wildness in.

So Kathryn had been first. They had started talking after Wesley’s performance—“Everyone loved him,” she said. “He sang and played his guitar. He was like some kind of ancient god, the music was so beautiful. Everyone wanted to talk to him.” But it had been Kathryn, wearing a knit dress that came past her knees, bare faced and plain, who had asked Wesley back to her house.

“And I never left,” said Wesley.

“Where did you live before?” Alice asked.

“Here and there,” he said.

“All that matters is that we’re here now. All of us,” Hannah Fay said, smiling at Alice. Alice had only been with Wesley and the girls for a couple of days, but she already knew Apple could be prickly, and Janie flighty, and Kathryn brusque, but Hannah Fay was always so warm and seemed genuinely glad that Alice had joined them. She and Alice were the same age, but Hannah Fay seemed wiser and older than Alice felt she herself was, and far older than Susannah and the other girls she’d known at school. Part of it was that Hannah Fay was here, on her own, living without parents, without an adult telling her what to do or where to go.

The ot

her part of it was that Hannah Fay was pregnant, her hands nervously touching the bump of her belly, fluttering around like uncontrollable, pale little birds. That first night, when Hannah Fay had been sitting at the table, Alice hadn’t noticed, and when Hannah Fay stood, and the curve of her stomach was revealed, Alice nearly gasped. Alice didn’t ask who the father was, and no one felt the need to tell her. She was beginning to think they assumed it would be obvious, that she should just know.

Alice smiled back at Hannah Fay before turning again to Wesley. “What song did you play for the concert?” she asked.

“One of my own,” Wesley said. He laughed. “There’s so much you don’t know about me.”

“I’m learning!” said Alice. “But I feel like I know you already. Really.”

“He’s very talented,” said Kathryn. “It’s unbelievable. He’s good at everything. Look at his photographs. And his paintings!”

“God, Kathryn,” Apple said. She was lying across the orange couch, her head back on the armrest and her legs stretched so that her feet were in Janie’s lap. Janie was pinching each toe and wiggling it, one by one. Apple didn’t even turn her head to look at Kathryn, just kept her eyes on the ceiling. “You are the world’s biggest suck-up. Did you know that?” she said. “And Janie, knock it off, please.”

Janie pinched Apple’s big toe even harder. “This little piggy,” she said.

“I thought the same thing myself,” Alice said quickly. “He played at the party we went to. Everyone loved him. I’d love to hear you play again,” she said, turning to Wesley, who affirmed it had been the right thing to say by picking up his guitar. She was proud of herself.

He strummed one chord, two. “Apple,” he said. His tone was warning, but he didn’t say anything else.

“Have you ever thought of making a record?” Alice asked. “Like professionally?”

“He tried once,” said Apple.

“He changed his mind,” said Kathryn meaningfully. “It wasn’t the right venue for his message. It needs to be visual, right, Wesley?” Wesley said nothing but frowned at his fingers plucking the chords, whether in displeasure or concentration, Alice couldn’t tell.

“We know,” Apple said.

Kathryn shot her a look. “I was telling Alice.”

“I outgrew music,” Wesley said. “But I have a lot to say, and I think a lot of it has to be said through art. I want to tell the world what it’s really like. I want to wake everyone up.” He turned to Kathryn. “I feel like taking a trip. I need to get out of my head a little bit.”

“Great idea,” said Apple, sitting up now. Kathryn left the room and came back holding a tin, which she handed to Wesley before taking a seat on the floor next to him.

“I’ll just make sure everyone stays safe,” said Hannah Fay from the oversized pillow on the floor where she reclined. “But I might go to bed early. My back hurts.”

“Stay,” said Wesley.

Hannah Fay pulled an elastic band off her wrist and twisted it around her red hair, like she was preparing for a battle, and yet her face looked rounder and younger than it had a moment ago. She rubbed her belly with one hand. Alice wanted to put her hand against that round curve too, feel how smooth it was. She imagined it would feel like a seashell.

All the girls were shifting now where they sat, pulling themselves up straighter, preparing, and when Wesley came to each girl, she would open her mouth and close her eyes, trusting and reflexive, and he’d place a tiny white tablet on her tongue before she would sink back to her original posture. His gait was slow and his face solemn as he went around the room, and Alice got the feeling they’d done this before.

“Open up,” Wesley said to Alice, and she didn’t hesitate. Mouth open, eyes closed, tongue relaxed. It reminded her of going to Mass as a little girl with her mother, not long after her father had died, how the priest would place that tasteless wafer on her tongue, and she would instinctively pull away. It had felt so intrusive: a strange hand reaching toward her mouth. But she was so receptive here, accepting what was offered to her. (Oh, Alice.) When she opened her eyes, she watched Wesley bite a tablet in half, swallowing one piece and placing the other back in the tin.

“That’s all, Wesley?” Apple asked, frowning. “Come on.”

“Worry about yourself, Apple,” he told her.

“He always takes less than us,” Apple said, looking only at Wesley, who met her gaze.

“Not all of us need our minds opened up the same amount,” Kathryn said, glancing primly at Apple.

Apple rolled her eyes, and Alice laughed. Her eyes looked so big, rolling around in her head like that. They used to be green, like Alice’s own, but they were suddenly dark now and getting darker. Like mud, she thought. Or the pits of cherries. Or the ink a squid shoots out.

“Why don’t you play something, Wesley?” Hannah Fay asked.

He played for hours. At first, Alice couldn’t move, even though she wanted to. She felt something inside her begin to stretch, and she realized it was her soul, it was reaching for Wesley, who played so well and looked so beautiful she nearly couldn’t stand it, but her body was trapping her soul. So she tried to tell her soul what it was missing. Music like a waterfall, like the ocean so early in the morning that there is no one out to hear it, rain like a gift to the earth after a drought, and then alternately, Alice realized, like fire. Both. Everything. It wasn’t only that Wesley was handsome. It was that he was handsome and talented and discerning, that he had looked around the whole world and he had picked her to be here. But handsome, yes. A strong and noble profile, like it was drawn by an artist with a gifted hand. Hands that could be gentle and strong, that could please her in multiple ways, a mouth that could do the same thing. Hands that held a camera, that held her, that painted, that played a guitar. Wesley stopped singing for a minute and grinned at her, a bright light in the darkness. “What?” she asked. “What’s so funny?”

“Just you,” said Wesley. “I’m so happy you’re here.”

“You’re talking out loud,” Kathryn said to Alice. Alice gasped, not because she learned she was narrating her private thoughts, but because she saw Wesley’s beard was growing, like a dark brown storm cloud fattening up with rain, and she realized the hours he was playing had become days, then weeks. “It’s almost time for Hannah Fay’s baby to come,” Alice said, ignoring Kathryn. “Isn’t it? Does it feel like a seashell when you touch it?”

“The baby?” asked Hannah Fay.

“Your stomach,” Alice said. “When the baby’s inside.”

Hannah Fay was still sitting on the floor, but around her the floor glowed and moved, and Alice remembered learning in biology about some kind of luminescent algae that made the water shimmer just like this, and she wondered how Hannah Fay had cast that algae around her. She pictured Hannah Fay holding out her pale index finger and pointing at the floor, a crackle of electricity zipping from the tip. Zap! Zap! Until she sat on a throne of light. Did the baby give Hannah Fay special powers? Would Alice have those powers someday when she had a baby? Did her mother have those powers too?

“I have so many questions,” Alice said. Behind her, she could feel someone braiding her hair, their fingers like crabs, scuttling in and out. She reached behind her to still the hands, but they kept going. In the distance, somewhere outside the house, she could hear a low, deep rumble. She knew it was a volcano. She knew that Wesley could make it erupt if he wanted to, and Alice both wanted to see the lava take down everything, swallow every house they’d passed by, the school, the library with all its books—and was frightened by the idea of it, scared it might swallow her up too.

“You can come feel my belly if you want,” Hannah Fay said, but she was suddenly far away, the luminescence around her now like the wink of a bright eye in the distance, and the plants had gotten so big and so green, so green that they were singing. And Wesley was singing, too, and she saw his guitar was really just an extension of his body, like a third arm, and that explained w

hy he was so good. It was like wondering why your hand was so good at having fingers. It was made to have fingers! The music tasted salty when Alice opened her mouth, and she remembered how Wesley had found her so long ago on the beach. “I’m a seashell,” Alice called to Hannah Fay, wherever she was. “Not you.”

“Put her to bed, Hannah, please,” Apple said. “She’s being annoying.” Apple and Janie were dancing in the middle of the room, having pushed the coffee table off to the side. They’d been laughing—hadn’t they?—just a moment ago. Apple extended her arm, and Janie twirled away and then back to her. They didn’t seem to hear the hungry rumble of the volcano. Alice knew she should stand up and go to the window, look for the plume of smoke, the tongues of fire, but she didn’t want to. If she didn’t look, she would be safe.

“She’s fine,” Wesley said. He had put the guitar down and picked up his camera instead. He walked to the window where the volcano was, and he took a picture of it, bravely, Alice thought.

“I guess you’ll put her to bed yourself,” Apple said.

“Maybe I will,” Wesley said, heading back to the girls.

“Let’s play a game,” said Kathryn. “Let’s play pretend.”

“I’ll be a wolf,” said Alice, because a seashell couldn’t really do much.

“Let’s play Afraid,” Apple said. “I like that one. I’ll start.”

“I’ll start,” said Wesley. “Kathryn, what are you afraid of?”

“Spiders,” she said. “Poverty. That I’ll lose the house somehow.”

“To spiders?” asked Apple, but Kathryn ignored her.

“Good,” said Wesley. “That was very honest. Hold on to that fear. Does the world seem more real now that you think about how much there is to lose?”

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves