- Home

- Alison Wisdom

We Can Only Save Ourselves Page 16

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Page 16

“Bearing his child,” said Apple.

“Right,” said Hannah Fay, rubbing her stomach again. “But hopefully not right this second.”

“How did your parents meet Wesley, anyway?” Janie asked. They each had an origin story, how they met Wesley, how they arrived at this house. Janie had been plucked like Alice had, but from a street filled with people just like her, young and down on their luck and crowding the streets and alleys of the district. “He hung out with us for a few days,” Janie had told her. “I watched him start to see me, like I stood out more than anyone else, even though all the other girls were all over him; he had his camera, of course, and they were all trying to get in his photos. Finally, he took me to this motel and washed my hair and my clothes and then brought me back here.” Alice listened, waiting for Janie to articulate what she herself had felt when Wesley found her, the inevitability of good things happening simply because the girls were special. But if Janie felt that same way, she didn’t say so.

Wesley and Apple struck up a conversation at a party a few hours away, and there was never a formal invitation but there was also never a question that she belonged with Wesley and the other girls and the house. The only one, to Alice’s knowledge, who made her way to Wesley on her own was Kathryn, the first of all the girls.

“Oh, Wesley was just passing through, and we sometimes took in travelers and gave them a room,” Hannah Fay said. “My parents and Wesley stayed up all night talking. I was sleeping at a friend’s house, and when I came home in the morning, my dad said, ‘Clara, this is someone very special, and I want you to listen to what he has to say.’ And I didn’t want to listen to a word my dad said because what does he know, right? But then I walked out onto the back porch—it overlooked a peach orchard we took care of—and there was Wesley, and everything smelled like peaches, and I stood with him and talked with him until I couldn’t stand any longer, and then I pulled him down next to me right on the ground, and when we stood up, the backs of our pants were all dusty.” Hannah Fay laughed. “Isn’t it funny the things you remember?”

“Clara,” said Apple. “I didn’t know.”

“That’s a sweet name,” Janie said. “If the baby’s a girl, you should name her Clara.”

“Wesley doesn’t like that name,” said Hannah Fay.

“Is that why he renames everyone?” Alice asked. “Is someone’s name not a true name if he just doesn’t like it?” She hoped she sounded jokey and silly, but it was a sincere question: she hadn’t been renamed, and it worried her, but maybe it was only because Wesley liked her name.

“No, it’s about the essence of a person,” Hannah Fay said. “He said I had a pure essence, and I needed a name that was more innocent than Clara.”

“Clara seems very innocent,” said Alice. “I’m dying to know why Apple got her name.”

“If you have to ask, you’ll never know,” Apple said.

“Apple is very secretive about her name story,” Janie said, “but I can tell you mine.”

“Yes, please,” said Alice. “I wasn’t sure if it was a faux pas to ask. It feels kind of like, I don’t know, like asking about someone’s dead sister.”

“I don’t mind at all! Wesley called me Jane Blue, Jane like Jane Doe because he found me on the streets and I didn’t have anyone claiming me or anything, and Blue for water because water gives life. He said he could tell I gave everyone around me purpose.”

“That’s so nice,” Alice said. “I wish I gave someone purpose.” (You did, Alice, and you could again. We see her. She’s waiting for you, still.)

“So he started calling me Jane B., and it always sounded like Janebee, and eventually it became Janie,” she said, “which I like much better.”

“What were you before?” Hannah Fay asked. Her face was bright with curiosity, and Alice could see Hannah Fay really didn’t know that the only version of Janie that Hannah Fay had ever known was this one. It had been a quick transformation for Janie, then, to go from a nameless girl on the street to something as precious and refreshing as clean water. If another girl joined them here someday, the way Alice had joined them, it was possible that girl would only ever know whoever the person was that Alice would become, whoever Wesley chose for her to be. No one she met from now on would ever know Alice again.

“Florence,” said Janie.

“Wow,” said Hannah Fay. “I really can’t see that at all. Florence sounds so prissy. You’re definitely a Janie.”

“Thanks,” Janie said brightly. “It’s kind of nice talking like this, isn’t it? About where we came from?”

“Only because of where we are now,” Hannah Fay said. “Imagine if none of us ever made it out.” They all looked around the yard where they sat, overgrown and wild. Alice breathed it in: there was a flowering tree in the corner with delicate white blossoms and there was a honeysuckle vine growing along the fence and there was the pungent smell of smoke in the air and in her hair, but she couldn’t help but think of us too. (Imagine sleeping in an alley and begging for food, imagine being sixteen in a creaking old house you shared with adult men and women you weren’t related to but also didn’t choose for yourself. Here, at home, we have private rooms and beds and hot meals; we have flowering trees and honeysuckle too. We do not play games. We think for ourselves, we let you keep the names you were born with. “Last names,” we could imagine someone arguing. Bev, perhaps. “We take the last names of our husbands.” Yes, we would say, but that’s an honor, a privilege. A different thing altogether.)

“Hannah Fay, did Wesley know you were”—Alice fumbled for the right word. A child? Underage?—“young?” she said.

“Yes, Alice,” Hannah Fay said. “He’s not blind. And he was very respectful, always. He didn’t even touch me for a long time, even though I told him I wanted him to. He kept saying no, it wasn’t right, I didn’t know what I wanted, et cetera, et cetera.” A breeze ruffled the bushes and blew a strand of her hair across her face, and she pulled it from where it stuck to her lips. “Finally, he went to my parents and asked them, and came back with a note from them saying it was okay by them if I did whatever I wanted with Wesley,” she said. “They said they assumed it had already happened, but they appreciated having the chance to give permission.”

“Oh my God,” said Apple, her dark eyes round. “Okay, Hannah Fay, that’s crossing some kind of line with your parents.”

“So it was like a permission slip,” Alice said. “Like you were going to the history museum with your fifth-grade class.”

“Yes,” said Hannah Fay stiffly. “If you want to reduce it to that, then sure. But it was really very meaningful.”

“I think it’s sweet, Han,” said Janie. “And if you think about it, it really isn’t that different from a wedding where your dad walks you down the aisle and gives you away.”

Hannah Fay sat up straighter and began nodding even before Janie finished speaking. “Yes!” she said, clapping her hands together and looking up at the sky, like she was relieved someone understood. “Right! That’s exactly right.” She rearranged herself again, loosening the cross of her legs so that her pink toenails peeked out again. “No matter how I sit, things keep falling asleep,” she said. “But I loved that, Janie. I know it’s traditional and kind of lame, but my family is so weird—seriously, if you met them or saw the homestead where we lived, you’d understand—it was so nice to feel like I was a normal girl with a normal dad giving me away to a normal guy, and now I’m going to have a normal baby and a normal life.” Abruptly, Hannah Fay stopped. “What, Apple?” she said. “Why are you looking at me like that?” Alice looked over at Apple, who had been quiet while Hannah Fay spoke, but now the quiet seemed less attentive and more like a sad, thoughtful kind of quiet.

“Nothing,” said Apple. “It’s all very sweet, but look around, Han. This isn’t a normal life. It’s a house filled with five girls and one man. None of us has a real job, except Kathryn. I know you know what some of us have done for money since we

’ve been here.”

None of them said anything right away. Alice hadn’t ever been asked to contribute any more financially than she had in the beginning, but she knew that Apple and Janie sometimes left together at night and came home after she was already asleep. The next day there would be plenty of groceries for the next few days or the lights would be back on or, once, Hannah Fay got the antibiotic she needed for a UTI. Alice had considered this, what she would do if Wesley asked her, or if Apple did. She had decided she didn’t really think she could. But maybe. If she had to.

Hannah Fay cocked her head to the side. “Well, yeah,” she said. “This part isn’t normal, but my relationship with Wesley is. When it’s the two of us, we’re just like any other couple getting ready to have a baby.”

“That sounds nice,” said Alice. “You’re a team together in a way the rest of us aren’t.”

“Yes,” said Hannah Fay, smiling at Alice. “But you’ll all be like the baby’s mothers too.”

“Aunts,” said Alice. Because she loved Hannah Fay, she already loved this baby, but she wouldn’t be anything like its mother. She would be the mother of her own baby.

“Aunt Alice,” said Hannah Fay.

“Aunt whatever Wesley will name me,” Alice said.

“We’ll have a party when he renames you,” Janie said. “Combination early birthday party for Hannah Fay.”

“I’ll rename you,” Apple said. “Phallus Alice. No, wait, Alice the Phallus is better.”

“Apple!” said Hannah Fay, but Alice laughed.

“Linda,” said Janie. “Because you’re pretty. Tiny. Magnolia. Tree. Flower.”

“Now you’re just naming things you see,” said Apple. “Mine was better.”

“Don’t worry, Alice,” said Hannah Fay. “Think about it like this: you’ve always had a true name, and Wesley identifying it doesn’t change the fact that it’s always been there. You’ve just never known what it was.”

“Thanks, Clara,” said Alice, and the girls laughed, and a few minutes later, they heard a rumbling close by.

“Is that thunder?” asked Janie.

“I think it’s the truck,” said Hannah Fay.

“Wesley,” said Alice.

“What’s the difference,” said Apple, and they all sat there, waiting for Wesley to come out and find them again.

Chapter Twenty-Four

THE NIGHT BEFORE Wesley was scheduled to meet with the owner of a very prestigious gallery, a man known for selling art to celebrities and socialites, he spread photographs over every surface in the house, like a gallery show, and the girls wandered through the rooms looking at the pictures, murmuring to each other and to Wesley about his genius, his craft, pointing out the ones they liked the best, though Alice knew that in the end, Wesley would choose his own favorites. “Hey,” Alice said, picking up one of the prints, which had another picture stuck to its back, one of Hannah Fay’s sharp facial profile contrasting with the soft roundness of her belly. “How do I know this girl?” Alice asked, showing him the top image, a girl with her hair piled high on her head, looking past the photographer. In her hands, she held an animal skull, grayish bone, something with a long snout. “Is that a skull?” Alice asked stupidly.

Wesley looked at it. “It represents death,” he said, but didn’t answer her other question.

But Apple peered over Alice’s shoulder at the picture when Wesley walked away. “That’s Sadie,” Apple said. “She lived here for a while.”

“I met her,” said Alice. “At the party Wesley took me to. What happened to her?”

“Oh, you know,” said Apple. “She just couldn’t hang.”

“Well, it’s a good picture,” Alice said. “Kind of creepy. He should bring it to show the guy.”

“He won’t,” said Apple.

In the morning, the girls watched him sidle up to the old truck, his portfolio in his hand. It was early, the sun watery and new in the sky, and he looked beautiful in the morning glow. “This is it,” he said. “This is when our lives change.” The girls waved as he drove off.

That night, they made dinner. They sat at the table with plates and silverware in front of them. The food—a stew made with everything that was about to go bad in the refrigerator and whatever Kathryn had pulled out from the garden behind the house, small green leafy things she barely washed, just ran under cold water from the faucet until the obvious dirt was gone—bubbled in a pot with a lid over it. Then it cooled, but the lid stayed on. “Wesley doesn’t like it too hot,” Kathryn said. “With the lid on, it’ll cool down a little, but still be warm when he gets here.”

The girls drained their glasses of red wine; Hannah Fay drank her glass of lemonade but wouldn’t have any more. “I’m afraid it’s going to give me heartburn,” she said, rubbing at her chest already. “Just water for now, please.”

Alice got up to fill Hannah Fay’s glass, rinsing it out before she held it under the tap, so that there wouldn’t be any lemony taste still clinging to its sides. She imagined herself pregnant, round belly tight with a baby pressing its hands and feet against her. She liked how she could see elbows and the curve of head bulging out of Hannah Fay. “It’s like an alien,” Alice had said when Hannah Fay showed her the other night.

Hannah Fay had laughed and said it was an alien, really, a parasite. Wesley had told her that was a rude thing to say about her baby, and Hannah Fay excused herself not much later. When she got up, Apple had taken her spot. She had lifted her shirt and showed off her tan, flat stomach. She had a tiny mole near her belly button, like a pinprick. “No babies in here,” she said. “Thank God.” Wesley had placed his hand against the plank of her stomach. “Not yet,” he’d said, and raised an eyebrow. “After all, we’re only as good as what we make,” he said. “And what’s better than making a baby?” Apple had laughed, and Alice had felt jealous.

Now, rogue water droplets dripped down the side of Hannah Fay’s water glass, wetting Alice’s hand, and she turned the faucet off. Then she lifted the lid of the pot and peered inside. The broth was reddish and thin. Potatoes and carrots bobbed in it like dinghies. Before they made it into the stew, the carrots had been whitish and dry, and the potatoes had begun to sprout little buds all over, like tiny, blind eyes. But the girls couldn’t afford to be picky about their food; they’d been growing even thinner, so if it was edible, they would eat it. Recently, they had even stopped going to the grocery store, and instead went behind the restaurants and bakeries and the cafeterias at the university when it was dark and late and found the dumpsters where every night food would get tossed out.

Alice was small and strong, and with Apple’s or Janie’s arms around her waist, she could rummage through the boxes and bottles and cans for any food in bags or containers, anything that didn’t look too unappetizing. It wasn’t as gross as she thought it would be, mostly broken-down cardboard boxes and swollen black trash bags, and as long as those hadn’t split open, the task was fine. They would take the food home, and Kathryn would hold it up and examine it under the buzzing yellow lights in the kitchen. When they saw it next, it had been transformed, chopped up into a soup or covered in sauce or garnished with curling shreds of the few vegetables she grew in their backyard. Like this.

Alice replaced the lid. “Shouldn’t we eat?” she called out as she walked back into the dining room. “He must be stuck doing something. Maybe finalizing everything with the gallery?”

“No,” said Kathryn, when Alice came back to the table and set the glass in front of Hannah Fay. “He likes us to eat together, like a family. Besides, he’ll want to celebrate when he gets back.”

“He could’ve called,” said Apple.

But Kathryn shook her head. “We didn’t pay the phone bill this month,” she said.

“Hannah Fay should at least get to eat,” Alice said. “She’s growing a human!”

“At least we think it’s a human,” said Apple, wrinkling her nose. But she winked at Hannah Fay.

“No ea

ting the stew,” said Kathryn. She straightened the silverware in front of her and put her hands in her lap. “Not till Wesley gets here. Hannah Fay, if you’re hungry, there’s a jar of peanut butter in the pantry.”

It wasn’t a bad evening, really. Alice was reminded of one night she’d spent in the library with Susannah. They had a giant test looming over their heads, but they couldn’t stop giggling, whispering stories about themselves to each other, or stories about people they knew or stories about people they never knew, only heard about, the tales that constituted the mythology of their neighborhood. (We understand this kind of closeness, remembering nights after most of the party guests have gone home, and it’s just a few of us, sitting at the kitchen table, a bottle of wine or gin in the middle. We would tell those same kinds of stories: about ourselves, about our friends, about the people who had faded away or left, leaving only legends in their places.)

Finally, when the wine was gone and the girls’ teeth and lips were stained crimson, when Hannah Fay had risked a second glass of lemonade, when the front door stayed closed and the rest of the house was silent and Wesley still hadn’t come home, the girls decided to go to bed. It was nearly midnight. They ate spoonfuls of peanut butter and washed and dried the spoons, put them back in the drawer, before saying good night to each other. In the kitchen, on the cool stove, the stew sat in the pot with the lid still on it. Kathryn had sighed, said she was sorry she couldn’t let the pot soak in the sink overnight.

“I dare you to tell that to Wesley,” Apple had said.

“I’m not sure what you’re implying,” Kathryn said. “But we have a relationship of mutual respect, and I certainly wouldn’t be scared to tell him he should have been home when he told us he would be.”

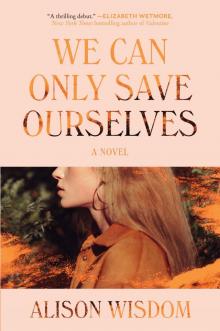

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves