- Home

- Alison Wisdom

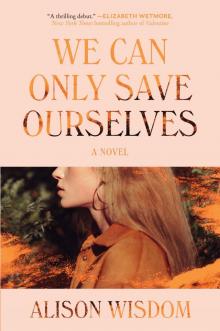

We Can Only Save Ourselves Page 17

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Page 17

“Yeah, okay,” Apple had said.

“He can’t call, Kathryn,” Hannah Fay said.

Later, Alice woke to a hand on her shoulder, a face near her own. “What is it?” she asked.

“He’s back,” said Apple. “And we’re going out.”

The living room was dark, the soft glow of a lamp providing the only light, and Wesley stood next to it, so that half his face was warmed to gold and the other half was obscured. In the living room, he instructed “dark colors” to no one in particular. Janie and Kathryn went around the rooms and gathered up navy-blue shirts, black dresses, and jeans and dumped them at Wesley’s feet in a pile that he then rummaged through, picking out outfits for each of the girls.

“Come here,” Wesley said to Apple. She wore a big T-shirt and nothing on the bottom, besides, Alice guessed, underwear. She had athletic legs with slim thighs and pretty calves, and Alice pictured her before Wesley, before this bungalow of women. She pictured Apple—no, back then, she was Betsy—gripping a field hockey stick and charging down a lawn of trampled grass, her dark hair whipping behind her in a braid, like the flag of a standard bearer marching into battle.

“Arms up,” Wesley said, and when she raised them, he pulled Apple’s T-shirt over her head and off, flinging it to the side. Her breasts looked, like the rest of her, firm and somehow athletic, making Alice think of tennis balls. Wesley looked at them, but did not touch, and dressed her himself in a black sweater and jeans that used to belong to Alice.

Apple kept one hand on Wesley’s shoulder as she stepped into the pants. They were too loose in the rear to be flattering, though when Alice had worn them back at home, they fit her tightly. She waited for Wesley to call to her, to peel off the shirt and shorts she slept in, to examine her body, to remember the feel of it under his hands, and to dress her, too, like he did Apple. Appreciatively, knowingly. But all he did was hand her a dark gray T-shirt and black pants.

“Okay,” he said when most of the girls were dressed. “Hannah Fay, stay here. You can wait up if you want, but you don’t have to.” She was sitting on the brown armchair, her sleep shirt bunching at the top of her belly, a thin border of skin showing above the top of her pants. Wesley bent down, put a hand on her roundness. Hannah Fay placed her hand on top of his and looked up at him.

“Be safe,” she said.

“We’ll be back soon,” he told her, leaning in until his forehead touched hers and her eyes closed. Janie stood beside him, and as he straightened up, he took her hand. The pair led the three girls out, and Alice, who was last, shut the door gently behind her. The street was quiet and still. Only a few blocks away, at the university and in the surrounding houses and apartment buildings, people would be awake and talking and partying, but here, their neighbors were asleep. (It goes without saying that we were asleep too. Not much good happens past midnight, this much we know.)

“So that’s what you were doing tonight,” said Kathryn, and Alice followed her line of vision. In the driveway, instead of the truck, sat a blue van.

“Are you taking us to soccer practice?” Apple asked.

“Yes,” Wesley said. “To Kathryn’s question. Apple, I’m ignoring you.” He clapped his hands together and nodded toward the van. “Everyone in,” he said. “Kathryn, you’re driving.” He tossed her the keys, which she caught in the little cup her hands made.

Alice, again, was the last, crawling into the farthest-back seat. It would have made more sense for Apple and Janie to sit back there since they got in first, but they sat just behind Wesley and Kathryn, whose heads were bent together in conversation. She was too far away to hear what they were saying, plus Janie and Apple were talking, too, about nothing, about stupid things. She wished they would shut up. They sat in the driveway. Alice buckled her seat belt, then unbuckled it.

Finally, Wesley spoke up, raising his voice so that it filled the van. He twisted around in the front seat so that he was looking at the girls in the back.

“It’s time for us to take action,” he said. “No more hanging around. So we’re going to do it, and you need to trust me. Okay?”

“What kind of action?” Janie asked. “What about the guy with the art gallery?”

“And the photos?” asked Kathryn, who had turned her body toward his.

“I changed my mind,” Wesley said. “He wasn’t the right person.”

“What happened?” asked Alice.

“The world is asleep,” Wesley said. “Practically comatose. Everyone wants the same old things. They don’t want to be challenged; they just want to be comfortable.” He sneered this last word, then sighed. “Things need to change,” he went on, “and it’s never going to happen unless someone makes them change. This place is shit. It’s not any good.”

“But we’re good,” said Kathryn. “You’re good.”

“Right,” said Wesley. “We are, I am. And someday we’re going to be very, very powerful. But for now, we need to shake things up a bit.” Alice worried about how they might do that, about what Wesley had in mind. She couldn’t see the faces of the other girls, but one or two of them must have looked concerned, too, because Wesley held up his hands and laughed. “Relax,” he said, grinning. “This is going to be fun, I promise.”

“Let’s go, then,” said Kathryn, and he clapped her on the leg.

“Let’s go,” he said.

Chapter Twenty-Five

KATHRYN DROVE UNTIL the neighborhood changed, then the city, but they couldn’t go too far, as the sun would be up in a few hours. Next time, Wesley said, they would go farther. They would go to a better neighborhood, where the houses were nicer and bigger, where the people had more money but they were less awake, less alive, where they had more to learn than others. But for now, he said, this one would do.

(This neighborhood didn’t look exactly like ours. This is a comfort, if a small one. Ours is comfortable but modest. We like to think that when people drive by, they imagine themselves there, their children playing, their husbands coming home from work, their friends complimenting their gardens. Maybe, they think, they could put a pool in. When they drive through our streets, they are not lusting after our homes; it isn’t that kind of neighborhood. There are some neighborhoods that are flashy, their houses voluptuous, almost indecent. These are the houses of the sleeping people, Wesley would say, the mausoleums of the blind. What would he say about ours? What would he say about us?)

They stopped, finally, at a two-story house with big windows, wide and long as film screens. It was the home of wealthy people but not the wealthiest people. This, Wesley insisted, was practice.

When they got up to the front door, Alice tried to peek inside one of the windows, but squinted as if the room were filled with too much light instead of darkness and more darkness. She thought she saw a piano, a big one like they had in the lobbies of fancy hotels.

It was Kathryn, surprisingly, who picked the lock, before stepping back, letting Wesley take her place. Alice thought of Andrew on his knees in front of the glass doors of the high school, his uncoordinated fingers fumbling around, telling Alice to stand back. Kathryn could have done it. Alice could have too.

“Don’t take anything,” Wesley said in a low voice, his hand on the knob. “Be very quiet,” he said. “If you see anyone, don’t touch them, don’t speak to them. Just get out.”

Wesley sent Kathryn in first, and they waited for her to return with a thumbs-up. “All clear,” she said. “Only one bedroom occupied, and it’s upstairs.” That seemed right to Alice, when she thought about it: they were sequestered away like royalty in a tower, as far away from the outside world, as far from the earth, as they could be. No one was safe, Alice thought. Wesley could get to them anywhere, and now she could too. All they had to do was want it.

She thought of that walk to the school, the dark houses they had passed. She remembered thinking those houses would be lifeless to her until she was in them herself, and now look, that had come true.

In the van,

Wesley had given them instructions for what to do once inside. “All we want to do is make them pay attention, wake up,” he’d said. “Do only what I’ve told you.” They started with the living room, with the couch and chairs. Wesley took one end of the couch, Janie and Apple the other, and they picked it up and moved it to the other side of the room. Alice and Kathryn put the chairs where the couch used to be. Alice rearranged some pictures. She picked one up and looked at it: a man and woman, attractive, not old, not young. Blond and smiling, an ocean behind them, but not their own. The Caribbean, Alice guessed. In another picture, the man stood in profile, shaking hands with a long-haired man. Alice was surprised to recognize the second man, and for a moment she couldn’t place him until an image of him on the TV screen at her mother’s house popped into her head—he was an actor.

Apple walked by, and Alice tried to get her attention. “Whose house is this?” she whispered, thinking of what Wesley had said about the gallery owner’s celebrity connections, but Apple either didn’t hear her or ignored her. She looked around. The walls held paintings, photographs; on the table right next to the picture of the long-haired man rested a series of small, ornate sculptures that looked to Alice like mutated creatures.

Apple and Alice picked up the coffee table, oval shaped and light, made from some kind of cheap manufactured wood, trendy and no doubt overpriced, and carried it carefully into the kitchen. They set it down, lifted the kitchen table up and out of the way, and put the coffee table in its place. The kitchen table took the spot of the coffee table. Alice went into the kitchen and opened each of the cabinets until she found a stack of plates. She pulled out all the drawers until she found one full of silverware. In a china cabinet, she found cloth napkins, neatly pressed. Then water cups, wineglasses. On her way out, she noticed a knife block next to the stovetop, the black handles sticking out, and she thought of how much danger was sitting right there.

In the living room, she set the table, slow and careful with the plates so she didn’t make a sound. She set a lovely table. (We are saddened to think of this eye, this attention to detail, gone to waste.) After putting the last fork in place, she studied the table for a minute; she still felt something was missing. So she went back into the kitchen, grabbed a knife from the block, and carried it back to the dining-room table. It was a short kitchen knife, the kind her mother used for peeling potatoes. She pressed the tip of its blade into the wooden surface, carving sharp letters into it. Then she walked out. The table, she knew, was perfect.

Janie and Apple swapped the bedding in the two first-floor guest rooms, the bedside tables, the lamps. Kathryn smoothed out a wrinkle in the rug. She arranged the pillows on the couch, just like she did at home. Wesley watched from where he stood, barely two steps into the house. “One last thing,” he said. “The pièce de résistance.” From behind his back he produced a rectangle, and Alice squinted at it in the dark.

“Is that one of your photos?” she asked.

“Leave it on the dining-room table, would you?” he said. Alice took it from him—it showed a slithering snake, in what looked to be the desert, cracked brown earth under its long dark body, and the brown toe of a boot, unmistakably Wesley’s, she thought—and placed it faceup on the table, right next to her own message.

Alice went back to him, standing close enough so that their arms were touching. “Very nice,” Wesley murmured. “Good work. I wish I could see their faces when they come downstairs in the morning.”

“Me, too,” said Alice. He pulled her to him so that he was facing her, and he kissed her, put his hands under her shirt. She hoped the other girls were watching, but knew already they were.

When he let her go, he gave a low whistle, and the other girls straightened up. He waved a finger in the air, a circular motion, and jerked his head to the door behind him. As they quickly followed him out, Alice thought she heard movement upstairs.

This time Alice cut to the front of the pack of girls, sliding open the door of the van. Behind her, Janie gasped. “Alice,” she said, and Alice turned around to face her. “Why do you have a knife?”

It was in her back pocket, flush against her backside, the point of the blade sticking out. She felt someone pinch it gingerly out of her pocket.

“It’s fine,” said Wesley. “We’ll get rid of it eventually.”

“But why do you have it?” Apple asked.

Because she needed to leave a message, just like Wesley had told them to do. She needed them to read it, open their eyes. Touch each letter she’d engraved: Wake up.

Chapter Twenty-Six

THE NEXT TIME, at a different, even nicer house, ran even more smoothly, and Janie was the one to hold the paring knife and stab it into the throw pillows on the couch. One of the pillows was furry and sat like a scared, square animal beside the others, and when Janie thrust the knife into it, Alice felt an abrupt sadness at seeing the fur and the feathers fly up and float back down. And then she remembered the pillow wasn’t alive, and besides that, its owners weren’t really alive either, not in the way they were intended to be. “They need some fear to wake them up,” Wesley would say.

It always made Alice shiver when Wesley talked about it, their mission, the desert: how eager he was and how confident. Though she knew it would be bittersweet to leave the bungalow, Alice found herself longing for the day they would venture out and start life anew. It wasn’t the bungalow that was important anyway; it was Wesley, the girls. Alice was a better, more authentic version of herself now, and her transformation had nothing to do with the house, the yard, the beds where they slept. (We have to disagree: a place is important too. A place shapes you. It protects you. Even that sad little bungalow they lived in was better than the desert—all that wide-open space, the blazing sun, and beneath it, dry earth, creatures that bite and sting. Where is the protection in that place? And what kind of person comes out of it?)

Alice and the others were a family now. And there were others out there like them, Wesley promised, but he hadn’t found them yet, though when he did, they would go and start building a new civilization, one in which they could make the rules, run the world.

In the second house, they left another photo, one Wesley had taken especially for the purpose. He had posed the girls in a row with their backs facing the camera and brown paper grocery sacks over their heads, hiding their beauty, he told them, from a world that didn’t deserve to see it.

After the third house and two weeks later, a fourth, Wesley came home one afternoon with a TV. Kathryn helped him carry it in, though it was small, and he could have managed it himself. They watched the news that night, hoping to see a story about the rash of break-ins around the city, but there was nothing. The only crime reported was the robbery of a gas station off the freeway. Wesley and the girls never took anything, only the knife from the first house, and that, Alice was always quick to explain, was an accident.

When the news report was over, Wesley stood up from the armchair and turned off the TV set. He rubbed at his eyes. “Let’s go outside,” he said. “Clear our heads.”

In the backyard, Wesley lowered himself into the green lawn chair, and the girls arranged themselves around him, with Alice at his right. Apple had cut the grass so that the blades were even and short, and it felt like the bristles of a rug. Alice kept running her hands over the grass.

“Maybe we should start taking things,” Kathryn suggested. “That might make them take us more seriously. Besides, we could sell them for cash.”

“No,” Wesley said. His voice was calm and thoughtful, as though he had already considered this himself and decided against it. “The last thing we need in this world is more stuff,” he said. “If we take anything, we might let it ensnare our minds and hearts the way it did for its owners.”

“But we need to up the stakes,” Kathryn said.

Across from them, Apple reclined next to Hannah Fay, whose belly rose up like a hill. She might have already been asleep, Alice wasn’t sure.

“I don’t know,” said Janie. “It doesn’t seem like a good idea. I like it the way it is.”

“It doesn’t matter what you like,” Kathryn said.

“Down, girl,” Apple said, holding up a hand. “Wesley, control your bitch, please.”

“Hey,” said Alice brightly, sitting up straighter and placing her hand on Wesley’s arm, hoping to change the subject. “When do you think I’ll get a new name?”

“When I can see who you truly are,” Wesley said. “I think I’ve almost got it.” He didn’t look at her but put his hand on her head, laced his fingers in her hair, rubbed her scalp.

“You’d probably better fuck her again,” Apple said. “I bet that will help.” She arranged herself so that she was sitting up now, chin lifted, and looking up at Wesley on his chair. She looked, to Alice, like a queen.

“I hope you aren’t jealous, Apple,” Wesley said without looking at her, his face tilted up to the night sky. It was like he was talking to the stars, the moon, the creeping vines. Apple had left those alone. “As you know,” Wesley said, “I fuck you as well, but I don’t have to. Don’t try to start shit, Apple, or there will be consequences.”

“Is that a threat?” Apple asked. “How can you threaten me if you chose me? Does that mean you were wrong about me? Wrong about something? About someone? Again?” Alice thought of Sadie.

He looked at Apple, and Alice saw in the set of his face, the flash of his eyes: Wesley, who didn’t experience the same mundane emotions other people did but instead felt things burn brightly inside him all the time, was suffering. He felt he had been wrong about something, hadn’t been able to wake up the sleeping people. But Alice knew he wasn’t wrong, and she’d convince him. She’d eat his suffering, drink it up until all that was left was the new world he’d promised them. Apple just stared back at Wesley, still defiant.

Hannah Fay sat up now too. So she hadn’t been asleep. “Apple,” she said, her voice soft and sweet, “no one’s threatening you. No one’s mad at you. We love you.”

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves