- Home

- Alison Wisdom

We Can Only Save Ourselves Page 26

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Page 26

“Of course you didn’t,” Susannah said. “But you had to know he would.”

“I didn’t,” said Alice.

“It’s a little selfish,” Susannah said. “All of it. Letting Ben get in trouble, leaving without saying a word to anyone.” She looked down, touched a silver screw in the swing with a gentle finger. “I didn’t even get to go to homecoming,” she said softly. “My last one ever.” Her pink dress still hung in the closet, on the velvety hanger they’d given her at the store. The bare shoulders no one had touched. When she had left Alice’s house the night the police came and she had told Mrs. Lange she needed to make a new plan for the dance, she’d gone home and watched TV with her mother and father instead, too angry and sad to see anyone or do anything else.

“I’m sorry,” Alice said. “I had to do what was best for me.”

Susannah looked up at her now, only her gaze rising, her chin still tilted down. “Okay,” she said.

“You’re going to grow up eventually too,” Alice said, reaching a hand over and putting in on Susannah’s knee. “I promise. It’s just—I got there first.”

“Is that what you think happened?” Susannah asked. “This is you growing up?”

Alice shrugged. “Yeah,” she said.

Susannah slid off the swing, and Alice’s hand slipped off her knee. “I should go,” she said. “I just wanted to come say hi.” She swallowed. “Tell you I missed you.”

“I miss you too,” Alice said, but that feeling she had when she saw her friend standing at her doorstep had dissipated. Or crystallized maybe, changed into something else. She missed Susannah the way she missed recess in elementary school, birthday parties with candles in cake, Santa Claus. Happy, sweet things that belonged in the past. “I won’t leave without saying good-bye again,” she said.

“Okay,” said Susannah. “See you later, then.” She left Alice on the swing but stopped halfway down the walk and turned around. “Can I come with you?” she asked. “When you leave?”

“No,” said Alice.

“Okay,” said Susannah again. But this time when she began to walk away, she didn’t look back.

Inside the house, Alice found her mother washing the lunch dishes. “Mama,” Alice said again, and her mother turned around, wiped her hands on a dish towel and pulled Alice to her chest. She thought she could feel her daughter’s heart beating, and what a miracle, how this was the same heart that she had given a home to in her own body eighteen years ago. How that heart kept beating and beating. How lucky she was to feel it, hear it.

“It’s hard to come home,” her mother said.

“But good?” Alice asked.

“The best,” she said.

“Am I good?”

Her mother let her go and took a step back, a hand on each of Alice’s shoulders.

“The best,” she said.

Chapter Thirty-Seven

HER MOTHER CONVINCED her to attend the annual holiday block party. It isn’t anything big or flashy, but it’s special. There’s homemade wassail and hot chocolate, caroling and gifts. Every year the Prices rent a machine that guzzles water and some kind of chemical and spits it back out as snow that falls over everyone who walks past their yard. Alice had been feeling slightly queasy all day and didn’t want to go and have fake conversations with people who didn’t understand anything about the world. “I’m too tired,” she had told her mother. “You go, and I’ll wait here.”

“That’s fine, honey,” Mrs. Lange had said. “I’ll stay here with you.” But when Alice watched her mother removing the sweater she had just put on, she felt overcome with a tender sort of feeling, like a bruising, somehow, of her heart, and she said, never mind, of course she would go. Besides, her mother had begun talking, vaguely, gently, about Christmas, the things she and Alice would do together. Alice responded to these hints in her own vague and gentle way, giving the kind of noncommittal answers that could be interpreted however the listener chose. She knew she couldn’t promise that she’d still be here, so accompanying her mother to the block party was, perhaps, the least she could do.

But as they went outside and she watched the children speed by on bikes, as she heard her mother’s laugh and the white lights on the houses twinkled as the sun set, she had to admit it was lovely here. It was a beautiful neighborhood. In the distance she could see Susannah, and she decided she would find her and try to be kinder, more understanding.

Before she could make her way to Susannah, someone tapped her on the back. Startled, she jumped, turning so quickly that her golden hair flew around her, bright in the twilight. “Oh,” she said, her hand over her heart.

There stood Ben Austin, whose mother, Audrey, watched him from a distance as he reached for a girl who did not deserve him. Audrey knew that though Alice seemed real before him, her shoulder firm and warm beneath his hand, the Alice he saw was only a mirage, a creation of his desperate mind and heart. Ben smiled at Alice, and his mother turned away.

“You’re really here,” he said. Now Alice smiled too; he seemed nervous. It was so different from the swagger and bravado of Wesley, but she found his uncertainty endearing, even attractive. What would it be like to be with Ben Austin? She imagined doing for him what Wesley had done for her—changing her, improving her. She could pull the strength and beauty from Ben, adorn him with it until he shone. How easy it would be to let him love her, to slip on her old life like a coat. There would be no other girls to compete with, none to argue with, but also, she thought, no other girls who would understand that aching love in her heart, the passion they shared for a common person. But still, it was tempting.

“I’m so happy to see you,” she said, and she threw her arms around him. He returned her embrace. We watched. We wanted to cheer, but then she pulled away from him, and we pretended we hadn’t been watching. “I need to talk to Susannah,” she told him. “But then maybe we could go for a walk and catch up?”

“Of course,” he said. He grinned, making a little dimple appear in one cheek. Alice had to stop herself from reaching for it, placing one gentle finger over it. A little breeze blew a piece of her hair across her face, and now Ben, too, thought of reaching toward her. “Aren’t you cold?” he asked.

“I am a little,” she said. “Okay. A walk later, you and me. I’ll find you.” She touched him on his shoulder as she brushed past him.

Susannah had disappeared from where she had been standing a few minutes ago, and Alice stopped in the middle of the street, first looking for her friend and then simply taking it all in. Down the street at the Prices’, children frolicked like little wild ponies under the spray of fake snow. Mags handed out cups of wassail and hot chocolate from a table in her yard, and in front of it, we stood together in small clusters, laughing and talking, toasting ourselves with the warm drinks in our hands. Later, we would switch to liquor to warm us up, when the children went to bed and the party became another kind of creature, a wild and merry beast. Alice scanned the street and sidewalk for Susannah, and her gaze landed upon her mother, who must have felt Alice’s eyes on her because she looked up. She gave her daughter a tiny, quick wink, without stopping her conversation with April. A breeze picked up once more, shaking the tree branches overhead, and Alice shivered.

As she stood there, we could see that she loved us again, how she loved this place. Here, she was a queen. We would let her be, we would let her play the role she was meant to have. She could be one of us again. She loved us, and we loved her in that moment too. It was the last time we truly, unequivocally, did.

Because she went inside her house. She needed a sweater, and it felt natural to walk through the door, like she’d never left. She wasn’t thinking of Wesley. She was thinking of Ben and Susannah, who loved her. Of her mother, who loved her. As she climbed the stairs to her bedroom, the ground shifted under her feet. The picture frames climbing up the wall beside the stairs crashed down. She heard glass breaking, and she grabbed the banister. A rumble, a crash.

A r

eality of living here, what we exchange for an idyllic setting: sometimes the earth shakes, it splits open.

When the ground stopped shaking—it was so fast, over in seconds—Alice walked over to the window. She saw us outside, most of us laughing and playing as if nothing had happened. Trees were still standing, houses. No fires, no gaping holes in the street. If she had looked more closely, if she had gone outside and back into our circles of conversation, she would have seen our surprise, would have watched us checking our bones, our pulses, would have heard us marvel at that small winter quake. Outside, we hadn’t felt it as keenly, though. It was a tremor, a spasm of the earth.

I’ll know, Wesley had said. I’ll know if you’re thinking of staying.

He isn’t who you think, Apple said.

A magician. A prophet. A god. The second coming of Christ. Perhaps he was something else still, possessor of a darker, more terrible power. This rumble and growl that shook her was a message, a reminder there was more he could do; there was more to who he was. Shaker of earth, finder of lost things, seer in the dark.

She went upstairs to her room, yanked open her desk drawer, and pulled out a sheet of stationery that read ALICE LYNNE LANGE at the top. She left her mother a note. It said, “I love you. Be safe and open your eyes. I’ll come find you, after.” It had been months, she realized, since she’d put anything down on paper, and her handwriting didn’t look the way she had remembered it, so different from the pretty looping “hello” she had written on Mr. Fielding’s blackboard. Her mother, when she found the note later that evening, refused to believe Alice had written it herself, and that if she had, she had done it under duress, given that shaky, uneven script. “This is a stranger,” she told us, holding it up, and we nodded but didn’t believe her.

Alice grabbed her bag, the money she had found in the house. She went out the back door, hopped a series of fences; we were all together in the street, so we didn’t see her scrambling over them, running across our backyards. When she got to the end of the street, the corner where she had met Carl months ago, in his little green car, she looked up and saw Bev. Bev saw her too. Bev, with her baby girl in her arms, who had wandered down the street away from the festivities to see if that would calm the baby, to see if perhaps she was overstimulated by the celebration. She had walked her with that slow bouncing gait that mothers develop when they hold their children, shushing in her ear, and the baby had fallen asleep. Now Bev didn’t feel in a hurry to get back to us.

Alice waved at Bev, said nothing. There was something final about that gesture, and Bev knew it was a good-bye, not a hello. She wondered if she should go after her, remind her what—and whom—she was leaving behind, but her own child woke up then, beginning to cry, and Bev looked down to comfort her. When she looked up, Alice was gone.

When Alice’s mother found the note an hour later, she wept and would not eat, would not sleep. Dr. Samuels had to come and give her a sedative. We took turns sitting with her until her sister arrived. She was like a paper doll, flimsy, no life in her limbs. We could fold her into anything we wanted, into whatever made us comfortable.

We would puzzle over that note for weeks. We still think of it. We wonder if her mother kept it. We would have burned it, buried it in the woods, thrown it into the ocean. After what? we wonder. If there’s an after, there must be a before. There must be a now. We are already awake. Our eyes are already open.

We worry something is coming.

Alice has gone again, and something is coming. We tell ourselves we no longer love her, but it’s possible that we do.

Chapter Thirty-Eight

AT THE BUS station, Alice hid in a bathroom stall for two hours before her bus was scheduled to leave, in case any of us came looking for her, but because her mother was too distraught to even think of checking the bus station, no one did, and eventually she boarded the bus and slept. She called the bungalow from a pay phone when she disembarked, but the phone at the house was still disconnected. Everyone would have been asleep anyway, and Alice, thinking of the driving man for the first time in weeks, didn’t want to hitch a ride. Across from the bus station was a twenty-four-hour diner, so Alice went there. She picked a booth by a window, ordered a bottomless cup of coffee, and watched cars and buses come and go in the gray parking lot until dawn began to break. She dropped a couple of crumpled bills on the table and left, a little bell above the door tinkling as she walked out. Now that it was morning, a few taxis were waiting to pick up passengers in front of the station, so Alice peeked in a window, relieved to see a driver who looked safe, or at least easy to escape from if need be, and climbed in. The new daylight was hazy through the car’s smudged windows, and jazz played over the radio, the driver’s wedding ring thumping on the steering wheel as he tried to keep time to the music.

When she finally got back to the bungalow, a stranger opened the door. “Hi,” the girl said. She was older than Alice, and her light brown hair was pulled into a thick ponytail. She was wearing a dress Apple often chose, but she was bigger on top than Apple, and the fabric there was stretched taut. Alice thought of Wesley handling each of those heavy breasts. “This is Jennifer,” Kathryn said, appearing behind her. “She got here a few days ago.”

“Hi,” the girl said, stepping out of the way and opening the door wider. She had deep dimples in her cheeks, like two small coins.

“My replacement?” Alice asked. She was still holding her bag, the strap digging into her shoulder. She had barely made it inside the house. The front door was still open behind her.

“We didn’t know if you were coming back,” Kathryn said. “But no, not a replacement.”

“Definitely not!” said Jennifer. Her voice had a chirpy quality. “The more the merrier, right?”

“Right,” said Alice. She looked around. “It’s still early. Where is everyone?” The house was quiet and sun soaked. Alice thought of a picture she’d seen in her science textbook of bugs trapped in tree sap, silent and golden.

“Janie went to that farmer’s market at the school to get a few snacks for the drive,” Kathryn said. “Wesley is picking up some people, some other girl, and a guy, I think.”

“Wait,” said Alice. “Another girl and a guy? Where’s everyone going to live? Here?” She took a few more steps into the house, passed into the living room. The other girls followed, and she let her bag slip from her shoulder.

When she turned around to face Kathryn, Kathryn looked surprised. “I thought you knew,” she said. “I thought Wesley must have gotten in touch with you. We’re leaving today.”

“But I thought we needed money,” Alice said. “I have it. Some.”

“We do,” Kathryn said. “But Wesley’s been very antsy. I guess we were going to go, money or not.”

Alice looked more closely at the living room. Everything was still there, the lamp on the side table by the couch, the little TV on the bookcase, the fat-leafed plants. She motioned toward all of it. “We don’t need it,” Kathryn said. “Bring some clothes and whatever shoes you have that will work well on the different terrain.”

She looked down to see that Kathryn was wearing hiking boots, and Jennifer was in leather sandals. Her toenails were painted burgundy and looked like round little grapes at the end of her feet.

The door of the study opened, and everyone looked over. “Hi,” said Hannah Fay, walking out. Her pale skin looked even whiter, pearly almost, and in her arms was a baby, small and pink and still. “She’s asleep,” Hannah Fay said. “But Alice, I heard your voice and had to come out right away.”

Alice opened her arms, and instead of embracing her, Hannah Fay handed her the baby, who squeaked at the transfer. She was warm and smelled—Alice breathed her in—like Hannah Fay. “Did Wesley find you?” Alice asked.

“I came back on my own,” Hannah Fay said. “I had the baby, and I looked down at her and saw Wesley and knew she needed to have a father and not just a mother.”

Alice said nothing, thought briefly of her own m

other, who, even alone, had been enough. She always had been. It was everything else in her life that wasn’t. She wished then she could tell her mother that. Maybe she could still tell her someday, the way that Hannah Fay still wrote to her own parents.

“Besides, Wesley is me,” Hannah Fay said. “I’m him. You know?”

“I do,” said Alice.

“It’s okay if she wakes up,” Hannah Fay said.

Alice looked down at the baby. She had full lips, the bottom one plump and pouting in sleep, and lots of dark hair. “What’s her name, Han?”

“Are you surprised to hear Wesley has an opinion about that? We aren’t naming her yet. So far, she’s just the baby, but I like to call her Sunshine, Bunny, Daffodil. I don’t know. Do I sound crazy?”

“A little. In a sweet way,” said Alice. “But I’ll be offended if she gets a new name before me.” When no one laughed, she said, “Kidding. She’s so beautiful, Hannah Fay. I love her already.”

“Isn’t she cute?” Jennifer chirped, and Alice felt a flare of annoyance.

“This hair,” Alice said.

“All Daddy,” Hannah Fay said, reaching over to smooth a lock of hair that didn’t lie flat. It was strange to imagine Wesley as a father. She thought suddenly of him wearing the cassock, Apple teasing him.

“Where’s Apple?” Alice asked. “I brought a sweater from my mother’s house that I thought she’d like.”

“Oh,” said Kathryn. “She’s gone.”

“Gone?” Alice repeated. “Where?”

“She left,” said Kathryn, as though nothing could be more obvious.

“I’m just going to step outside,” Jennifer said. “Excuse me.” Before she did, she placed a hand on each of Kathryn’s shoulders and squeezed.

“I’m going to change her diaper,” Hannah Fay said, sliding the baby from Alice’s arms and disappearing back into the study. Alice’s skin felt cold in her absence, and she wanted, badly, inexplicably, to have her back.

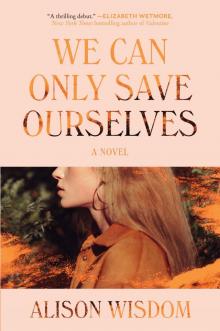

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves