- Home

- Alison Wisdom

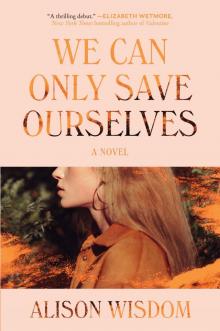

We Can Only Save Ourselves Page 27

We Can Only Save Ourselves Read online

Page 27

“Why would she leave?” Alice asked. “She told me she’d be here when I got back.”

Kathryn shrugged. “She and Wesley had a fight when Hannah Fay came back,” she said.

“About what?”

“Apple painted a picture of Hannah Fay and the baby,” Kathryn said. “And Wesley thought she was mocking him.”

“How?” asked Alice, confused. “Apple can paint?” Even absent, here was Apple forcing Alice to alter the image she held of her in her head, changing herself again.

“Well, it was really good,” Kathryn said. “I’d show you, but Wesley destroyed it. Anyway, you know Wesley doesn’t ever paint people, and he thought Apple was showing off, trying to prove some point about what a bad painter he was.”

Alice thought of what Apple said the night before Alice left for her mother’s house. He doesn’t paint people because he doesn’t know how. “It’s possible,” she said.

“There’s more,” said Kathryn. “Wesley asked her why he wasn’t in the picture with Hannah Fay and the baby, and Apple said it was because he might not stick around, he might leave again, just like he had left his son.”

“Oh, Apple,” said Alice.

“It was bad,” said Kathryn, nodding. “But she was asking for it! She knew what she was doing. She wanted to get him all riled up. Anyway, they fought, and in the morning she was gone. No note, nothing. She just vanished.”

Alice thought again of her mother, of the note she had written, and felt glad she had left her with that small gesture of kindness. “What did Wesley say?” she asked.

“He saw it coming,” Kathryn said. “He said he’ll miss her, but it’s better without her.”

“Wow,” Alice said. “Are you sure she left? What if she didn’t mean to leave forever, she just went out in the morning and then something happened to her?” A sudden image of a girl with a broken shoe entered her thoughts, but she couldn’t get a hold on it. It must have been Apple she was thinking of, the time when Wesley punished her and she hitchhiked to different cars until the sole of her shoe peeled off.

“Wesley would know,” Kathryn said. “He said she’s gone for good and we shouldn’t worry about her because she’s fine. Now, go get whatever you want to bring,” she said. “We’re leaving as soon as he gets back.” Kathryn began to walk into the kitchen and then paused, calling over her shoulder. “Don’t forget tampons,” she said. “We won’t be able to go to the store as easily when we get there. And my period started a few days ago so yours probably did too.”

The bedroom was messy, the bed unmade. Maybe Apple had left in the night, leaving Janie to wake up alone. Apple always made the bed in the morning, smoothing out the quilt and arranging the pillows so they sat proud at the headboard. Alice rifled through the community pile of clothes, picking out what she liked the best but also what seemed appropriate for their new home at the ranch—jeans, lightweight tops, a sweater. When they left, they wouldn’t be coming back here. It wouldn’t be safe. It would be a war zone, Wesley had told them. Think about that. Imagine that.

Pants and shirts and blouses, socks and bras and shoes missing mates, shoes with laces untied. Most of her own clothes were there in the stack, except the yellow dress Apple had adopted. She saw that Apple had left a heavier pair of sneakers in the closet, and Alice stepped out of her slim white tennis shoes and put them on instead. They felt bulky but powerful on her feet—she imagined stomping on scorpions, the heads of snakes.

In the bathroom, she rifled through the drawers until she had a handful of pads and tampons. It always bothered her that her cycle had synced up with Kathryn’s, of all the girls, like nature was trying to tell her something about herself she didn’t want to hear. But Kathryn was wrong—her period hadn’t started a few days ago. It hadn’t started at all. She put her hands on her stomach. She looked at herself in the mirror but she looked the same. Pretty and light, like an angel. A goddess.

It didn’t feel right to leave the room untidy, so Alice straightened up. She pulled the quilt tight on the bed, and placed the pillows like Apple always did, and when everything looked as neat as it could, she went into the living room to wait.

They took turns riding shotgun beside Wesley at the front of the van on the drive to the desert. He drove meanderingly, pointing out what different places would look like after the war began. “Bombed out,” he said about the university. “Empty,” about the ocean. “Charred,” about the trees. “When the war is over, that’s when we’ll come back, and we’ll rebuild, just us, our own little family. We’re the chosen ones, see? You are, I am. We’ll remake the world into what it’s supposed to be.”

“When will it start?” asked Jennifer. She was sitting behind the passenger seat, leaning forward. The other two new people, a girl named Rosie and a guy who called himself Dallas, sat in the far back, bumping along as Wesley drove. Janie and Hannah Fay were there, too, of course, but they were quiet, even the baby in her mother’s arms. Alice worried about Janie, how she was faring without Apple. She resolved to take better care of her; she could dance with her and laugh with her, the way Apple did. She could hold the ice to Janie’s cheek when things went south with Wesley. She could do that for her.

“It’s taking longer than I thought,” Wesley said now. “Everyone is so asleep, like deep asleep. But we’re going to kick things off, you know? I have a plan.”

By the time Alice took her turn in the front seat, the land had turned tan and yellow and dusty. The sun was setting, a fiery orange, loose around the edges, a threat, like it might drop out of the sky and scorch the earth. Begin Wesley’s war that way. She rolled her window down. The air was dry and sweet. “I wonder if we’ll see coyotes,” she said.

“Probably,” said Wesley. He had one hand on the steering wheel, holding it steady under his thumb. He was relaxed, and Alice thought back to that first ride out to the bungalow, the energy thrumming under his skin.

“I’m excited,” Alice said. “Are you?”

“I am,” he said.

Alice stuck her arm out the window. Wiggled her fingers in the wind. There were so few cars out here, so few other travelers. Her mother and her aunt and uncle had taken her out to the desert once before, to a national park, they told her, but when they got there, it wasn’t like any park Alice had seen before. The trees were spare and sparse and crooked, like skeletal fingers of underground giants punching upward, trying to break through the earth. They were going to go camping, but her mother wanted a proper bathroom, so they stayed at a motel and drove into the park first thing in the morning. Alice counted salamanders, jumped off rocks, ran away from her mother when she tried to put sunscreen on her bare arms, on her white cheeks. “I almost forgot,” she said to Wesley. “But I came here once when I was little.”

“Hey,” said Wesley, glancing at her. “Want to hear something you’re gonna like?”

“Yes,” Alice said. “Actually, I have to tell you something too. Something I think you’re going to like.”

“What is it?” he asked, looking over at her again, eyebrows raised, one hand loosely on the top of the steering wheel.

Alice laughed. “You first,” she said.

“I figured out your name,” he said. “Your true name. Are you ready?”

Alice stuck her head out the window, gave it a shake in the wind like a dog, and closed her eyes. Dust, wind, light, all streaming in. New life growing. She pulled herself back into the van, leaned against the seat. “Ready,” she said.

Chapter Thirty-Nine

THE DESERT IS a wild thing. It could have eaten her, stretched open its jaws and swallowed her into its belly, a pit under the dirt and rock. We wonder about her. We tell her story. There is danger here, she taught us that. Things that will take our children, things that will change them. Things that threaten us. We won’t let it happen again. We’ll keep watch, we’ll fight harder, we won’t let the wrong ones in. If we have to, we’ll lock ourselves up for good, for the good of everyone, for our neighbors.

Bev holds her daughter’s hand as they walk down the street, Tim running in front of them. She’d just called April’s house to see if she and Billy wanted to play, but it was Eric who answered the phone. He was home sick from work, his voice scratchy and tired. “I suppose you need April to take care of you,” Bev said. “I was going to see if she and Billy wanted to meet outside, but if it would help, you can just send Billy over and everyone can get a break.”

“Actually,” Eric said. “She’s over at Charlotte’s.”

“Ah,” Bev said as if she understood and this was perfectly clear, but she did not, and it was not.

“You should go over there too,” Eric said. “You know Charlotte likes everyone to know what a good hostess she is.”

“I think maybe I will,” Bev said. She wished him well and hung up. Bev called out to Tim, scooped up her girl, and when they made it outside, she let her walk on those chubby pigeon-toed feet, clutching her hand tightly.

Charlotte’s house sits at the mouth of the neighborhood, and nearby there are construction workers busy laying brick and mortar. Billy and the Price twins huddle at a safe distance, hands in pockets. One of them holds a basketball. Without a word to his mother, Tim runs over to join them. “Bev,” Charlotte says. “What a pleasant surprise!”

“Eric told me you were here,” Bev says.

“I was going to call you,” April says.

“It’s okay,” Bev says.

“The boys are obsessed with the construction,” April says as Bev walks up. “They’re hoping they can steal a drill or something.” She grins at Bev, hopes she will forgive her, or better yet, that she hasn’t noticed. But as Bev sits cross-legged on the lawn, the baby already pulling at the blades of grass, she gives April a polite smile, cordial but not warm. Bev’s teeth are the same, the lips are the same, but it isn’t her normal smile, and April feels her stomach clench, before she remembers that she has nothing to be ashamed of. It was Bev who’s at fault, Bev who let Alice Lange go the second time. “You could have stopped her,” April had said when Bev told her about seeing Alice leave.

“Do you really think so?” Bev asked. She was neither frowning nor smiling, and April couldn’t tell if Bev was amused, skeptical, or if she genuinely wanted to know if April thought it was true.

“You could have tried.”

“The baby was crying,” Bev said. “I had to take care of her.”

It’s okay, April tells herself now. People change, drift apart, even here. We can’t save everything. To tell the truth, we don’t want to.

“Christine Pittman is very interested as well,” Charlotte says disapprovingly as the child bikes up to the boys. The women watch Christine say something to them, point at the workers.

“Heavy machinery is very interesting,” Bev says. “All those teeth.”

“Enough to cut a limb off,” says Charlotte. “Or a finger.”

“Exactly,” says Bev. “Isn’t that the appeal?”

“Not for me,” says Charlotte.

On the other side of the street, Mrs. McEntyre and Sweetie walk past. Sweetie pulls the leash, yanking her owner’s arm straight as a board, barking at the workers or at the boys or at the women or at the trees, the sky, the squirrels. Mrs. McEntyre notes the women and their feet: Charlotte Price’s crossed at the ankle, in slip-on shoes, April’s jittery and nervy in white canvas sneakers, Bev’s in espadrilles, despite the chill in the air. Those are shoes for summer days. A swell of power from Sweetie, and Mrs. McEntyre is pulled forward again. The women wave at her.

A burst of laughter comes from the square of boys watching the workers, and the women look over as their children break apart and scatter. Christine is laughing too. One of them passes the basketball to another.

It’s been almost a year since Alice disappeared again, before she escaped us once and for all. We have kept everyone safe, even installing the streetlights to fight the darkness, but it’s not enough. Hence the small team of men here with saws and drills, measuring, cutting, building. Soon those materials will come together to be a gate and a little booth where a man in a uniform will sit and keep a lookout. He will be nice but not too nice. He will only let in those who we want let in. The man who took Alice away, with the boots and the beard and the pale eyes—he would never have made it past the guard, and she would still be here. In a way, this effort is done in Alice’s memory, this booth and gate a monument to who she used to be.

There was a close call once, not long after Alice disappeared the second time. The body of a girl was found a couple of hours away, buried in a shallow grave. Police were working on identifying her, and out of either desperation or ineptitude, released some details to the public. She was wearing a yellow dress, the color of corn silk. Foul play, they said. Weapons: something blunt, then something sharp and small.

Alice’s mother didn’t watch the news, but her sister called. I could swear I’ve seen Alice in that dress, she said. The last Thanksgiving I came. Could that be right? Her voice was shaking. I’ll call the police myself, she said, so you don’t have to. When she called back, she said they told her it was best if Alice’s mother came up there herself. I’ll go with you, her sister said. But Mrs. Lange told her no. She couldn’t put it into so many words, but if it was Alice, she wanted to have a final moment in which the world she occupied consisted only of the two of them and no one else.

She drove two hours to a somber building in another city, near the college she and Alice had visited once. A police officer guided her past the front desk, into a room where the light was blue and cold, and she couldn’t bring herself to focus on anything, so she was left only with impressions: stillness, steel. A figure covered in a white sheet. She nearly threw up. The officer with her wouldn’t even leave, though Mrs. Lange asked him to, tried to explain how she felt about seeing Alice alone. I’m going to pull the sheet back now, he said, if you’re ready.

It wasn’t Alice, just some other poor girl, Mrs. Lange said on the phone to her sister. They could have told you on the phone this girl had dark hair. It would have saved me a trip.

Thank God, her sister said.

Mrs. Lange wept anyway. On the drive home, she couldn’t stop thinking about that girl beneath the sheet, who was missing, once, just like Alice, just like Rachel Granger. She felt bad for how callous she had sounded, telling her sister she had wasted her time driving to see this girl who, in the end, wasn’t her daughter. But she was someone’s daughter once, and Mrs. Lange felt suddenly thankful a mother had come to see her in that cold place, even if it wasn’t her own.

Still, we do not trust Mrs. Lange. She only cared about her daughter, would have done anything to keep Alice with her, given anything, would have sacrificed any one of us. Knowing this, perhaps, is why we don’t reach out to her now.

“Lots of neighborhoods are doing this,” April says, nodding at the construction. “That’s good, don’t you think?”

“Better safe than sorry,” Charlotte says. She looks at Bev, who realizes she is supposed to say something.

“Absolutely,” she says.

“It’ll be nice if we plant some flowers around the booth when it’s done,” April says. “Something that blooms year-round.”

“Marigolds,” says Charlotte.

The truth is Bev thinks Alice would have left anyway. Even if Bev had stopped her, grabbed her by the hand, and marched her back to her mother. She would have found someone else, somewhere else, and she would have gone. She hopes her daughter, who is right now pulling herself up as she holds on to the arm of Charlotte Price’s chair, will leave someday too. Not with that man or any other man like him. No woman like him either. She doesn’t want someone to lead her girl away; she wants the girl to take herself and make her own way. Bev will go with her if she has to. They can leave together. This, she thinks, could work. Light out for the territory, go somewhere new. They could start over, have new lives. They could escape. Her husband could come, and Timmy, of course. They could be pio

neers somewhere else, could build their own small world together.

We cannot recommend this. We are working to make things safe and good here so that we don’t have to leave, so that everyone who is here can stay. Out there is a wilderness we just cannot tame. We can’t take care of the whole world, after all. We can only save ourselves.

Acknowledgments

THANK YOU TO my agent, Stephanie Delman, for your warmth and encouragement, your guidance, and your insight. I am so lucky to have you on my team; you are truly the best!

To my editor, Emily Griffin—every phone call, email, and edit from you has been so generous and kind, and I am so grateful to have gotten to work on this book with you.

To the team at Harper Perennial: Jane Cavolina and Suzette Lam for their careful consideration during copyedits, and to Joanne O’Neill for the gorgeous cover.

To you, reading this book! What a miracle that you are here. I am so grateful.

Thank you to my teachers and friends at Vermont College of Fine Arts, where I learned how to take myself seriously as a writer. Thank you to Bret Lott for telling me I really should just try writing a novel, and to Wedgewood Circle for the financial support to do so.

To Britt Tisdale, my best writer friend, for fielding every text message from me with good humor and love, for talking me down when I’ve needed it, and for always building me up. No matter what the problem is, I always feel better after talking to you.

To Cameron Dezen Hammon, who has believed in my work from the very beginning and has never let me get away with selling myself short.

To Brittni Austin for listening, for always being in my corner, and for making me laugh.

To Nsen Buo for loving me, for loving my children, for being the person I most like to sit on my couch with.

Thank you to Claire Wisdom, my sister and my best friend. Very few people get to have such a good sister or such a good best friend, and I’m very lucky to have both those things in the same person.

We Can Only Save Ourselves

We Can Only Save Ourselves